As global economies begin their recovery from the pandemic, there is an emergence of inflation, while governments grapple with elevated debt levels

by Anna Fedorova

As news of the global pandemic emerged in March 2020, a wave of sell-offs roiled global stock markets and investors feared a prolonged downturn. But this was not to be. Even as the pandemic spread and intensified and economies all but ground to a halt, markets soared to new highs. This market rally was fuelled by the unprecedented amount of central bank stimulus in response to the crisis. Global monetary and fiscal stimulus over the past 15 months has amounted to US$30.5tn, equivalent to the entire European and Chinese GDP, according to Bank of America (BofA) Global Research, and far more than the cumulative total of 2009-2018.

As economies across the globe begin to open up as a result of successful Covid-19 vaccination programmes, the unleashing of pent-up demand is creating inflationary pressures. Earlier in the year, inflation fears filtered into investor expectations, with the yield on US 10-year treasuries rising from below 1% in January to 1.74% on 19 March (according to FT data), though two months later yields came down once again, sitting at 1.28% as of 23 July.

On the other hand, commodity prices have been on the rise as demand returns, with the price of Brent Crude up 70.31% over the year to 23 July, to US$73.78 at the time of writing.

Meanwhile, recent months have seen a jump in bond yields globally, dubbed a ‘taperless tantrum’. Reminiscent of the ‘taper tantrum’ in 2013, when bond yields in the US soared after the Federal Reserve (Fed) signalled plans to reduce the pace of its monthly bond purchases, this time yields have been rising without any such rhetoric. Since the start of 2021, the US 10-year treasury yield has risen from 0.93% (on 4 January) to 1.28% on 23 July – an approximate 0.4 percentage point increase. Most other bond markets have followed suit.

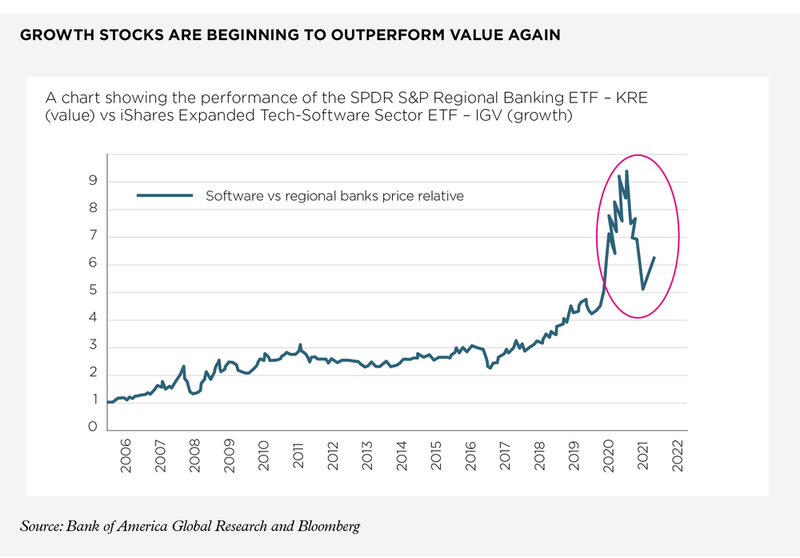

Meanwhile, growth stocks are seeing a comeback, after a rotation into value during the first half of the year, according to BofA data.

A key question for investors is whether inflation can be expected to rise in the longer term, and what will be behind this rise if so: the double whammy of monetary and fiscal stimulus and pent up consumer demand, or perhaps the unlocking of supply chains for corporates? If investors subscribe to the case for higher inflation, it would be prudent to continue rotating into value style investments now while inflation expectations are dampened. Some 72% of fund managers responding to BofA's Global fund manager survey, published 15 June 2021, believe inflation is transitory.

Between a rock and a hard place

However, it would be prudent not to dismiss the risk of rising inflation, according to Rahul Mathur, investment manager of the GAM Star Global Rates Strategy. Speaking on CISI TV’s Global macro outlook webinar on 11 May 2021, he warns the current “low inflation mindset” is “reminiscent of the mid-1960s”, as US inflation began its rise into double digits. The last time the year-on-year Consumer Price Index (CPI) in the US jumped above 5% (the level in May 2021) was back in the summer of 2008, but annual inflation has not reached these levels since 1990.

Data coming out of China has added to global inflation fears, with its producer price index rising 9% in May 2021, according to the National Bureau of Statistics of China. This is reported to be the fastest year-on-year increase since September 2008. In the UK, inflation, at the time of writing, has overshot the Bank of England’s (BoE) 2% target to 2.5%. Outgoing BoE chief economist Andy Haldane warned in a May 2021 interview with the Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation that inflation in the UK could spiral out of control.

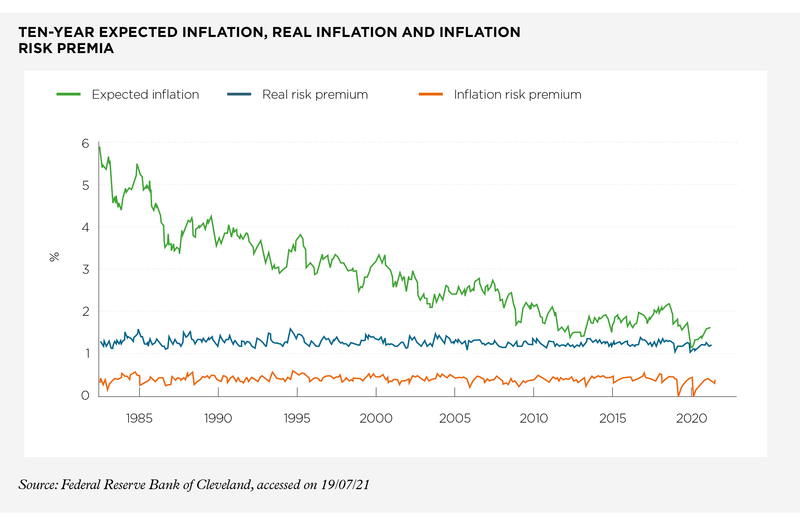

But Neil Shearing, chief economist at Capital Economics, is of the opinion that the inflation risk is short-term and price rises should begin falling back again in the next three to six months. Low labour bargaining power, technological advances and rising debt levels all have a deflationary impact on the economy. Inflation expectations also remain anchored (at just 1.58% in the US over ten years, according to Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland data), while the low yield on US 10-year treasuries suggests markets have brushed off the threat.

Central banks across developed markets, including the European Central Bank, the Fed and the BoE, have also taken a decidedly dovish stance so far. In a policy meeting held on 15–16 June 2021, the Fed raised its headline inflation expectations to 3.4% from 2.4% in March, but maintained a position that the spike is “transitory” and voted to keep quantitative easing (QE) and interest rates unchanged.

The BoE, meanwhile, has also kept the size of its balance sheet unchanged at £895bn, though this decision was not unanimous. Haldane was the lone vote in support of tapering bond purchases by £50bn to combat the threat of rising inflation, while eight other Monetary Policy Committee members – led by Gertjan Vlieghe – believe tightening too soon would be dangerous.

On the other side of the coin is the huge rise in debt as a result of the unprecedented stimulus packages introduced during the pandemic. According to the Institute of International Finance’s (IIF) May 2021 Global debt monitor, global debt remained elevated at US$289tn in Q1 2021, US$24tn of which is pandemic-related stimulus, according to the February 2021 Global debt monitor. This highlights the difficult position central banks find themselves in, trapped between the need to raise interest rates to control inflation and the pressure to keep them low to reduce the burden of servicing government debts.

Are emerging markets similarly exposed this time around or will the US dollar remain weak against emerging markets currencies?

If inflation continues to rise, central banks will eventually be faced with the problem of raising interest rates. The Fed is now projected to raise interest rates for the first time in 2023, a year earlier than previously forecast. Yet with debt levels at historic highs, will policymakers be able to raise interest rates safely without causing economic collapse?

The first step before raising interest rates would be to slowly begin unwinding QE, but governments across the world continue using fiscal and monetary support to boost economic activity. The notable exception is China, which is aiming to reduce its deficit from above 3.6% in 2020 to 3.2% in 2021. The current backdrop has sparked warnings against raising interest rates too soon, including recently from US Democratic lawmaker Carolyn Maloney.

According to Mathur in the CISI TV webinar, this predicament could even jeopardise central bank independence if government officials speak out against interest rate rises. If central bank independence is undermined, the risks of hyperinflation could be higher than economists predict. In fact, these concerns were precisely what led to the signing of the Treasury-Fed Accord in March 1951, which granted independence to the US central bank. Over the years, various studies have supported the thesis that central bank independence helps control inflation. This includes a 1993 paper in the Journal of Money by Alberto Alesina and Lawrence H Summers and a 2008 study by Alex Cukierman in the European Journal of Political Economy, both of which find a negative correlation between inflation and legal central bank independence.

The debt problem

The ‘taper tantrum’ in 2013 was particularly painful for emerging market economies, many of which hold large amounts of US dollar-denominated debt. Rising interest rates in the US meant rising costs of servicing this debt. IIF figures show emerging market government debt levels are up 15% since the end of 2019, with total emerging market debt now amounting to US$86tn, or 246% of GDP. Are emerging markets similarly exposed this time around or will the US dollar remain weak against emerging markets currencies, dampening the impact?

The debt problem is not specific to emerging markets, however. Total debt in mature markets amounted to US$203tn as of 31 March 2021, according to the IIF, with government debt continuing to rise in Q1 2021. And this is unlikely to change any time soon, according to Emre Tiftik, director of sustainability research at the IIF, who tells The Review that “continued policy support is crucial for recovery and thus debt accumulation is set to continue broadly across all sectors and jurisdictions”. The much-vaunted ‘wall of savings’, which could spur a return to growth, meanwhile, is tiny by comparison – around €400bn (or just 3% of GDP) in Europe, according to Allianz, for instance.

Financing a green recovery could provide a way out of the debt mountain for global governments

This creates new risks that investors must factor into their portfolios. Neil Shearing divides these into two categories: financial stability risk, where vulnerabilities in the financial system are exposed, and default risk (including the risk of hyperinflation). He believes it is unlikely that the solvency of governments in developed markets will be called into question, but there could be pockets of default risk in emerging markets, he says, pointing to countries such as Ethiopia, Kenya and Sri Lanka, which are facing defaults amid rocketing debt servicing costs. However, though Neil agrees a period of austerity will be needed to bring down debt levels, he says, “I don’t think there will be austerity as large as in 2008”. From an investor’s point of view, caution is warranted when investing in areas exposed to these risks, particularly emerging market equities and debt, while inflation expectations must be a key consideration for portfolios.

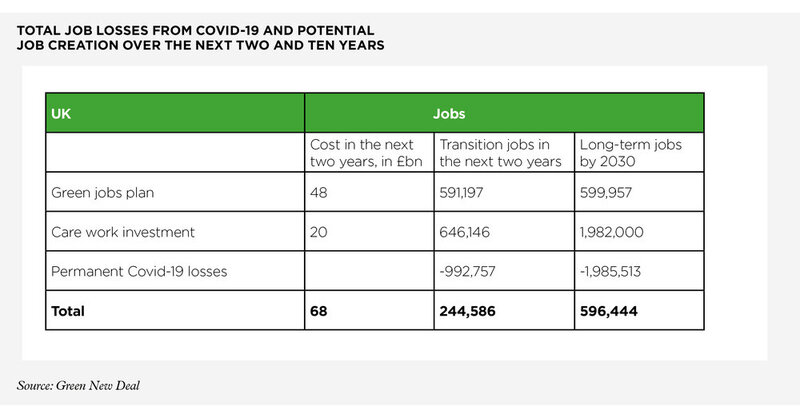

Nonetheless, as climate policies top global agendas in the year of the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, financing a green recovery could provide a way out of the debt mountain for global governments. A report by non-profit Green New Deal, for example, estimates that a green recovery plan in the UK could create 1.2 million new jobs within the next two years and more than 2.6 million during the next decade, more than replacing the jobs lost during the pandemic.

Speaking at Ethical Finance 2021, a summit held in June which was supported by the CISI, Dr Rhian-Mari Thomas, chief executive of the Green Finance Institute, emphasised the importance of a “green recovery, ensuring that the stimulus measures are being designed to accelerate the transition to a resilient low-carbon economy”. “There are no logical coherent high-carbon pathways to growth,” she said.

The European Union is already taking the lead, having committed some €850bn to a green recovery over two programmes: NextGenerationEU and Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE). However, some emerging market assets could suffer in the transition, with the IIF estimating that a 10% increase in climate vulnerability would increase emerging market sovereign spreads by an average of 100bps.

Adjusting portfolios

Against a backdrop of rising government debts and staring down the barrel of US interest rate increases, emerging market equities could once again be vulnerable to sell-offs. In 2013, the MSCI Emerging Markets index fell more than 16% between 8 May and 24 June, in US dollar terms.

James McCormack, managing director and global head of sovereign and supranational ratings at credit rating agency Fitch Ratings, warns this time there is the added risk that emerging markets will recover more slowly than developed counterparts. Speaking on the IIF Global debt monitor webcast on 13 May 2021, he says: “Historically, 1998–99 was the last time when developed markets grew faster and that was a very challenging time for emerging markets. I’m not saying we’re in the same scenario, but it does speak to a gap that is emerging in terms of performance between developed markets and emerging markets.”

Other risk assets could be vulnerable in the short term, according to Ben Seager-Scott, head of multi-asset funds at investment firm Tilney Group. However, over the medium-term, he believes equities still look attractive, since they “benefit from having some level of inflation pass-through”, while “the capacity to increase earnings and the increase in capital expenditure could help boost productivity and profitability in the medium term”. Cyclical businesses that benefit from a growth in global GDP, as well as essential businesses and those with strong brands that can pass on the costs of inflation are well placed to deliver strong returns in the current environment. Sectors such as technology, pharmaceuticals and luxury goods could fit the bill. Given markets are yo-yoing between growth and value assets, however, it’s important to think carefully about the exposure of the portfolio to these two styles.

When it comes to fixed income, investors must tread carefully, and many are already adjusting portfolios to reflect the inflationary environment. According to BofA’s June Global fund manager survey, allocation to bonds is at a three-year low at a net 69% underweight, while holdings in stocks are at year-to-date highs with a 61% overweight.

Investors will certainly have to be more careful when building their asset allocations to avoid exposure to unanticipated risks

Matthew Stanesby ACSI, managing director at Close Brothers, says: “In an inflationary environment it’s the interest rate risk component of a bond that is impacted, as inflation eats away at the real value of future interest payments. Long-dated fixed interest bonds become less attractive and can result in negative returns for holders.”

Accordingly, the Close Brothers multi-asset funds have reduced their allocation to bonds and increased holdings in alternatives instead to replace the income-generating component. Investments that could work as replacements include real assets, such as infrastructure and renewable energy, both of which can also help investors meet their environmental, social and governance commitments through job creation and supporting the move to net zero.

However, Matthew says there is still a place for fixed income in a diversified portfolio, with credit and inflation-linked or floating rate bonds more favourable than long-dated fixed interest. “Strategic bond funds might be a good place to allocate to, but remember – it’s a very disjointed peer group, so it’s vital to do research and due diligence to uncover the sort of fund that can and will make use of the flexibility,” he adds.

Andrew Eve, investment specialist in the M&G Bond Vigilantes team, also sees “idiosyncratic opportunities” in emerging markets debt, where valuations remain at “reasonable levels” and real yields are still elevated versus developed markets, as well as investing in currencies correlated to global trade or inflation. The bottom line, Andrew says, is to be “active, not passive” in bonds in the coming years. “Active investors can react more quickly to a changing world, but also take advantage of dislocations in the bond market,” he explains.

Given the economic backdrop, investors will certainly have to be more careful when building their asset allocations to avoid exposure to unanticipated risks. This includes looking for diversified sources of income, but also ensuring that the equity portfolio is exposed to areas that are likely to emerge from the pandemic as winners. A focus on assets that facilitate the green recovery from the crisis will be a key part of a winning strategy for investors this year and beyond.