Responsible investing is moving rapidly to its next level of sophistication. Simple negative screening models – which avoid investing in companies or sectors with poor sustainability credentials – are starting to look like very blunt instruments. Even more sophisticated environmental, social and governance (ESG) scoring models are beginning to look dated.

According to Dr Christopher Kaminker, head of sustainable investment at global investment manager Lombard Odier: "ESG data and strategies are now very good at identifying businesses with good or bad business practices. But these strategies tend to stop there. It’s why so many ESG funds include oil and gas companies – because they focus only on business practices and not business models and their interaction with nature." But leading investors are starting to make their investment decisions through the lens of nature.

Lombard Odier launched its Natural Capital strategy in November 2020. Christopher describes the plan as a "high conviction listed-equity strategy", which is inclusive of ESG attributes, but goes further than that, looking to "capture the opportunities presented by investing in companies that harness and preserve nature", such as biorefineries, which use wood-based materials to produce bio-based products ranging from bioplastics to medical products, and to "minimise the risks associated with things like biodiversity loss" through the use of satellite imagery to track deforestation and identify at-risk supply chains.

Mirova is an asset manager that has been investing with debt and equity nature-based strategies (in mostly unlisted investments) for around seven years. These include land degradation neutrality (sustainable land-use projects that will reduce or reverse land degradation through sustainable agriculture, sustainable forestry and other land-use sectors), climate, sustainable oceans, Brazil biodiversity, and agri3 (bridging-type investments to support proof-of-concept in innovative agriculture that will de-risk projects and unlock bank finance).

Gautier Quéru, head of the Land Degradation Neutrality Fund at Mirova, says that many investment institutions have been "blind to nature", but over the past five years he has seen perspectives changing thanks to "huge leaps forward in research around the risks and opportunities". The challenge now, he says, "is to turn these big-picture macroeconomic studies into investable actions". The emergence of new nature-themed investment strategies, such as those of Mirova, Lombard Odier, and others, are now making these investable actions more accessible to many more investors.

When we start to dig into some of this research, the ramp-up Gautier is seeing is no surprise. "Nature-related risks and opportunities are of a scale material to investors", says a Lombard Odier report published in January 2021: Investing in Nature.

Biodiversity's influence

The economics of biodiversity: the Dasgupta review (final report), by the UK government and led by Professor Sir Partha Dasgupta, was published in February 2021. The final and interim reports were commissioned due to evidence of humanity degrading nature at an alarming rate. The final report says: "Simultaneously, the material standard of living of the average person in the world has become far higher today than it has ever been; indeed, we have never had it so good. In the process of getting to where we are, though, we have degraded the biosphere to the point where the demands we make of its goods and services far exceed its ability to meet them on a sustainable basis. That is ominous for our descendants and suggests we have been living at both the best and worst of times."

"Bees do not send invoices, but they should"

That warning hits very close to home when we consider just how dependent humans are on the goods and services that the final report refers to, which are those defined by The Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services as:

- provisioning services: materials and energy including food, fresh water, fuel, biochemicals and pharmaceuticals (medicines, food additives), and genetic resources (genes and genetic information used for plant breeding and biotechnology)

- regulating and maintenance services: including maintaining the gaseous composition of the atmosphere; regulating climate, water flow and diseases; pollinating plants; and offering protection against storms (forests and woodlands on land, mangroves and coral reefs on coasts)

- cultural services: including spiritual experiences and opportunities for recreation.

Dasgupta points out in the final report that biodiversity influences the productivity of ecosystems that deliver these services, while the interim report details how biodiversity has been eroded. For example, in the past four decades, there has on average been a 60% decline in the populations of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians, with declines across biomes and regions. And the estimated number of wild bee species (prolific pollinators) fell from 6,700 in the 1950s to 3,400 in the 2010s. According to the Lombard Odier report mentioned above, bees support the pollination of crops worth up to US$577bn per year. Christopher Kaminker comments: "Bees do not send invoices, but they should."

In a similar vein, it points out that air pollution generates US$3.5tn in annual health costs and yet "we do not value the clean air supported by our soils and forests [and] we rarely put a price on the value of carbon sequestration provided by our forests, even though this helps us to mitigate an expected escalation in climate-related damage linked to global warming".

"Although nature is overexploited, it is also underutilised"

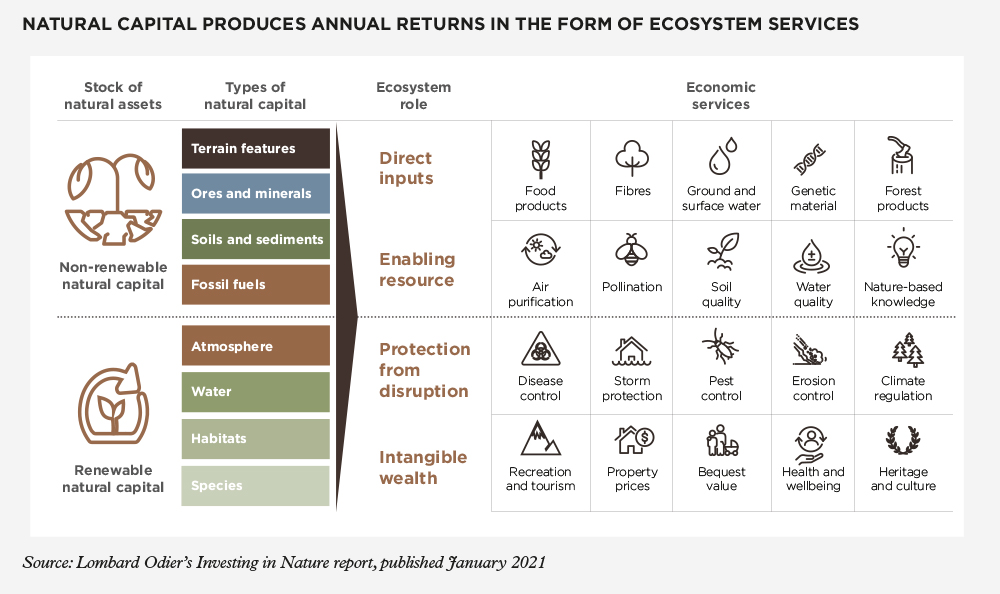

These examples perfectly describe what has become known as ‘natural capital’ which according to Investing in Nature: "includes all the renewable and non-renewable resources in our biosphere, including clean air and water, fertile soils and sediments, biodiversity, and finite mineral and fossil resources." The interim report of the Dasgupta Review states: "Nature is referred to by economists as natural capital, akin to produced capital (networks of roads, rows of buildings and so on) and human capital (combinations of health, knowledge, and skills)."

This capital produces annual returns, similar to the returns we talk about in the investment world, as it delivers nature’s services (provisioning, regulation and maintenance, and cultural services). According to Lombard Odier's whitepaper: "Nature provides many of the direct inputs that support our primary industries, but also provides the enabling and protective services that drive our economy, and itself represents an intangible form of wealth."

Investing in Nature introduces the economic concepts of stocks and flows, describing nature as a stock of natural capital (for example oceans, forests, soils, and the atmosphere) that can be expanded through good management or lost through neglect. These stocks generate benefits and services to society, which could be thought of as flows: fish from oceans, timber from forests, minerals from soils and air from the atmosphere.

It is not a difficult intellectual concept to appreciate that these stocks and flows have economic value, but it is an extremely difficult exercise to assign a value to them in dollar, pound or euro terms. The whitepaper states: "Although nature is overexploited, it is also underutilised. Our failure to value natural capital has led us to turn a blind eye to its decline, and kept us from grasping its economic potential."

Nature-based risks

The World Economic Forum and PwC have quantified the economic dependence on nature. The January 2020 report, Nature risk rising: why the crisis engulfing nature matters for business and the economy, concludes that US$44tn, more than half of the world’s total GDP, is moderately or highly dependent on nature.

Unsurprisingly, the report identifies ‘primary’ industries such as food and beverages, agriculture and fisheries, and construction as those with the highest dependency on nature. But perhaps less intuitive is its conclusion of how dependent ‘secondary and tertiary’ sectors are too, including chemicals and materials; aviation, travel and tourism; real estate; mining and metals; supply chain and transport; and retail, consumer goods and lifestyle. These sectors have less than 15% of their direct gross value added (GVA) highly dependent on nature, but they also have "hidden dependencies through their supply chains", amounting to more than 50% of GVA. For example, an airline has no direct exposure in its supply chain to the degradation of a coral reef, but if tourists stop travelling to a degrading reef, it most certainly does.

The financial services sector has begun to explore the transmission of nature-based risks to its own organisation-level risks – which are commonly addressed in financial reports or interactions with regulators, such as stress tests on banks.

De Nederlandsche Bank (the Dutch central bank and financial sector supervisor) and the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency conducted extensive research on this and in June 2020 published the report, Indebted to nature – exploring biodiversity risks for the Dutch financial sector. It finds that biodiversity loss poses material financial risks to many financial institutions.

These include:

- physical risks, such as financing companies that are dependent on ecosystems (fisheries or timber sectors)

- transition risks, such as financing companies whose products become outlawed or uneconomic (coal miners)

- reputational risk, from financing non-environmentally friendly industries or projects (as happened to HSBC in January 2021)

- litigation risk, such as claims for compensation for biodiversity-related losses

- systemic risk, such as creditors, investee companies, or insureds suffering losses at the same time (due to any of the above risks), causing widespread losses to banks, asset managers, or insurers.

Nature-based opportunities

Gautier Quéru says the risks above are applicable to nearly every investment, whether labelled sustainable or otherwise, and should be considered by all investors. Nature-based opportunities, however, are most commonly available through thematic investing strategies.

Further examples of these investing themes are provided by another prominent nature-based investor, HSBC Pollination Climate Asset Management, which is aiming to raise US$1bn for a fund to invest in themes such as: sustainable forestry; regenerative and sustainable agriculture; water supply; blue carbon (carbon captured by oceans and coastal ecosystems); nature-based biofuels; or nature-based projects that generate returns from reducing greenhouse emissions.

"If you consider that agriculture is responsible for 70% of the world’s water withdrawals, that’s a huge opportunity for investors"

Christopher highlights two interlinked points that are providing investors with new opportunities: studying nature itself, and access to new technologies.

He says: "Nature has figured out the very best way to do what it does over two billion years of evolution. Take artificial photosynthesis as an example: photosynthesis is a hyper-efficient process that has been fine-tuned by nature over time, and it has largely been a natural wonder to us. But because of things like digitalisation, computing power, and DNA sequencing, we can start to unlock some of the secrets of how nature generates so much value, and 200 years after we understood the scientific principles, we now have the artificial leaf." According to Investing in Nature, two-thirds of newly developed drugs are based on or inspired by natural products.

Christopher continues: "Sensors, satellite data, and robotics are now allowing us to create a step change in the productivity of agriculture and water use." For example, drones and other intelligent machines are being used to farm autonomously, monitor crop health and nutrient levels, to map diseases and pests, and sensors are being used to identify water leaks. "If you consider that agriculture is responsible for 70% of the world’s water withdrawals, that’s a huge opportunity for investors." says Christopher. Businesses that are responsible for improving the efficiency of use of such a scarce resource are operating in a potentially enormous market and are contributing to huge productivity gains.

2021: A landmark for nature?

The year has kicked off on a positive note for nature-based investing.

In January, Prince Charles launched the Natural Capital Investment Alliance with founding members HSBC Pollination Climate Asset Management, Lombard Odier and Mirova. The Alliance aims to fast-track the development of natural capital as an investment theme, and to engage the US$120tn investment management sector "and mobilise this private capital efficiently and effectively for natural capital opportunities". It has set a specific aim of mobilising US$10bn towards natural capital themes across asset classes by 2022.

The momentum is likely to gain further impetus with the Fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15), scheduled to take place in May 2021 in Kunming, China. It is expected that new targets for the preservation of biodiversity are likely to be agreed. Christopher says: "Policymakers are stepping up. There is no Paris Agreement for biodiversity but we think COP15 will give us something along those lines."

Another development the financial sector will want to watch is the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD). This is still in the establishment phase but a working group with 73 members (including many of the world’s largest financial institutions, governments, and thinktanks) has been established to plan a two-year programme. This will look to, according to TNFD's website, "resolve the reporting, metrics, and data needs of financial institutions that will enable them to better understand their risks, dependencies and impacts on nature. In collaboration with the corporate sector, reporting frameworks will be developed in 2021, and tested early in 2022 before being made available worldwide."

These developments are bound to increase the profile of nature-based investing. As they do, more and more investors will recognise the nature-based risks their portfolios are exposed to (on an individual investment level and on a systemic level) and start to recognise the scale of the opportunities as well. We could see biodiversity move up alongside climate to the very top of the investing agenda.