While the UK Stewardship Code is influencing the standard-setting in other countries, there are still obstacles to overcome

by David Burrows

The UK Stewardship Code 2020 defines stewardship as "the responsible allocation, management and oversight of capital to create long-term value for clients and beneficiaries leading to sustainable benefits for the economy, the environment and society". It sets high expectations for how investors, and those that support them, invest and manage money on behalf of UK savers and pensioners, and how this leads to sustainable benefits for the economy, the environment and society.

In short, the onus is on investment managers to pay more than lip service to environmental and societal factors and to actively demonstrate their commitment in how they behave. There is room for conflicts here. If asset managers and investment managers are to influence the companies they invest in to put sustainability at the heart of their business; they are arguably clouding the waters if some of their money still supports polluters of one sort or other.

The fact that investment in environmental, social and governance (ESG) funds broke through the £800bn barrier in November 2020 (according to Morningstar) indicates just how far ESG credentials now figure in investors’ minds.

While there are many positives to be drawn from this and incentives for companies to adopt best stewardship practices, the reality is that there are no global standards in place to ensure companies in different areas of the world are moving in a positive direction at the same pace. Can countries learn from each other more?

"In the US, there is a suspicion that stewardship is part of a left-leaning agenda"

The Asset Management Taskforce's Investing with purpose report, published in November 2020, highlights progress made in the UK – notably the UK Stewardship Code 2020. Could this lead a global movement to better stewardship? How will it encourage good practice in the challenging jurisdictions of Moscow and beyond?

Colin Melvin, managing director at responsible investment specialist Arkadiko Partners, thinks the UK, with its recently updated stewardship code, has laid down the marker for others to follow.

"The UK’s stewardship code is world-leading in that it is what most other codes in the world are based on. For instance, the Japanese Stewardship Code has been modelled on the UK version and is notably similar," says Colin. Both codes encourage signatories to explain their rationale for some or all voting decisions, and require consideration of ESG issues, but the Japanese code doesn’t mention climate change, which features prominently in the UK code.

Gen Goto, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Tokyo, points out some subtle differences in a blog for the University of Oxford Faculty of Law.

"The Japanese Code aims to change the behaviour of domestic institutional investors to exert pressure on entrenched management as actively as foreign institutional investors. This goal of the Japanese Code is more compatible with the (fiduciary) logic of stewardship than that of the UK Code, although the former still focuses on the corporate governance of Japanese companies rather than the interest of Japanese ultimate beneficiaries."

While any parallels between the Japan and UK codes may be encouraging, the ideal scenario of standardised, global stewardship principles adhered to by all is some way off. The fact that in many instances such codes are voluntary is one obstacle; another is that countries view stewardship differently. "In the UK, stewardship is not seen in any way as political," says Colin, "but in the US, there is a suspicion that stewardship is part of a left-leaning agenda." While he accepts that there are investment firms in the US actively looking to improve stewardship standards, it is purely done on a voluntary basis.

UK stewardship principles

To provide context and to better understand what progress needs to be made globally on stewardship, we need to explain the practical steps laid out in the UK Stewardship Code. The code sets high expectations on those responsible for managing the long-term savings of the UK public. The three main pillars are:

- strengthening stewardship behaviour

- stewardship for clients and savers

- creating an economy wide-approach to stewardship.

Essentially, the investment manager must take account of client and beneficiary needs, communicating their stewardship and investment activities and outcomes. They will need to demonstrate how they have integrated stewardship and investment, incorporating ESG issues, and climate change, to fulfil their responsibilities. They will also be required to produce an annual stewardship report explaining how they have applied the code.

The concern expressed in the Asset Management Taskforce’s report (and an area the code attempts to address) is that "some investment managers don’t prioritise stewardship in their governance and culture and don’t comprehensively integrate stewardship across their investment process. This can result in a disconnect between stewardship teams and investment teams".

Rather than stewardship being a core focus of the relationship with the client, other considerations such as cost and recent performance tend to drive portfolio selection decisions. Colin says that the emphasis needs to shift from a transactional relationship to a custodial one where creating long-term value is the clear goal.

Group participation

Creating an economy-wide approach to stewardship requires all participants – that is not just investment and pension fund managers, but investment consultants, proxy advisers, index providers, credit rating agencies and data providers to play their part. They all have significant influence over the responsible allocation, management and oversight of capital.

They should all demonstrate how their services support effective stewardship outcomes. Finally, to gain sufficient traction, respective governments need to show their commitment to the stewardship agenda.

Catherine Howarth, chief executive of responsible investment charity ShareAction, is fully supportive of the UK’s 2020 Stewardship Code and the best practice it calls for, but says that there is considerable room for progress in the three areas outlined.

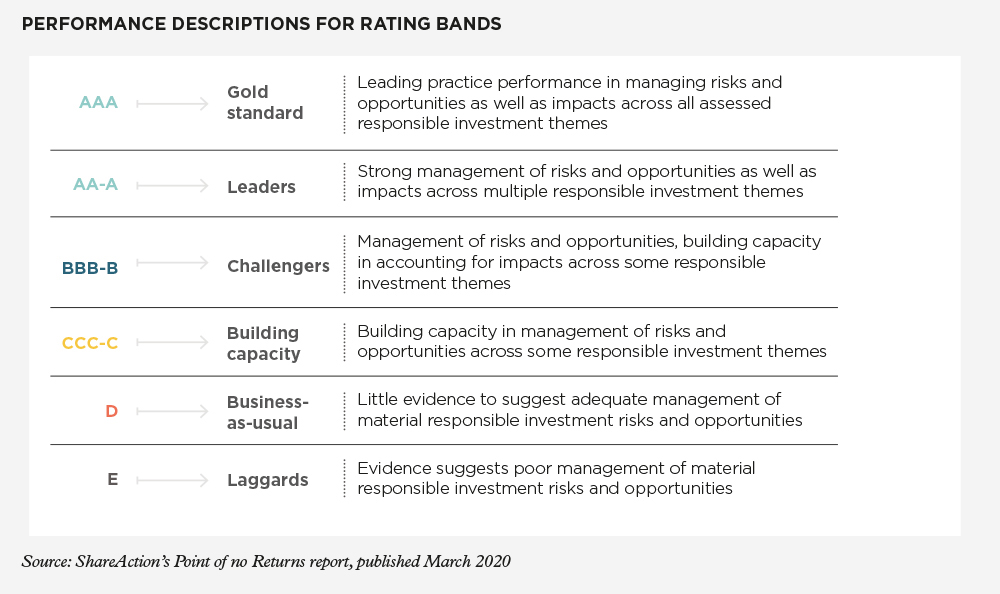

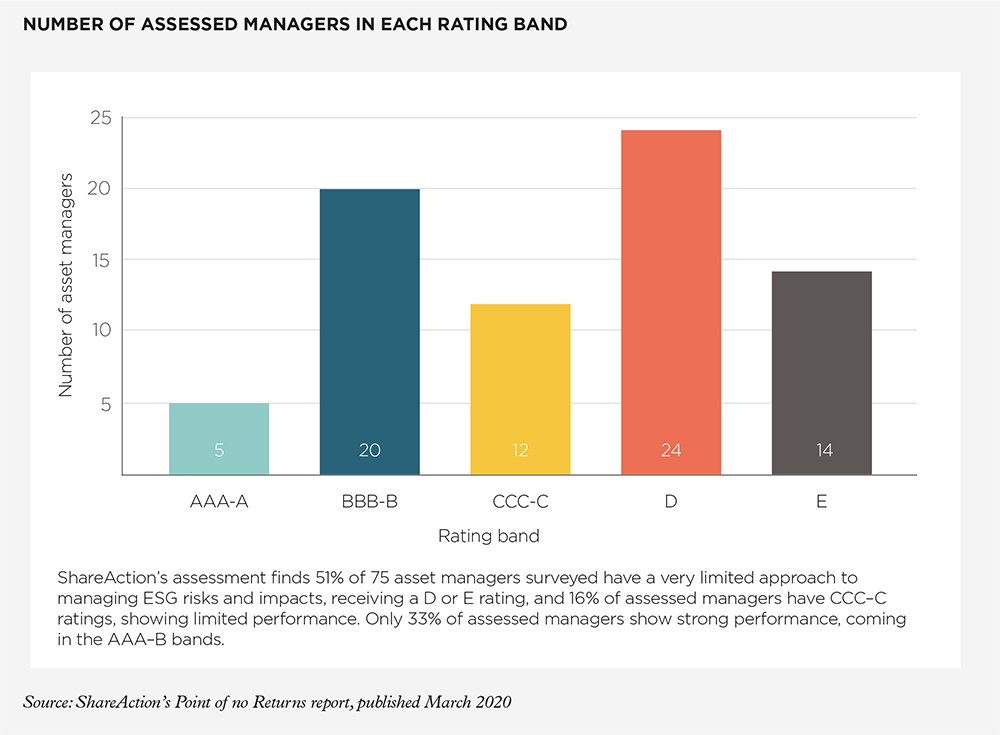

"If we take ShareAction’s 2020 ranking of the world’s largest fund managers on their responsible investment performance, which looked in-depth at stewardship, we see UK managers doing well but not better than other European fund managers. Large US fund managers perform poorly; Asian fund managers are laggards but are looking to raise their game."

These current rankings are perhaps unsurprising given the strong regulatory signals on sustainable finance at the EU level – such as the EU’s sustainable finance agenda – and at member state level – for example, Article 173 of the French Energy Transition Law, adopted in August 2015, and the Dutch Climate Agreement, published in June 2019.

In stark contrast, the strong policy signals in recent times from both the former Trump administration and the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) that climate change is not a priority, makes it unsurprising that US asset managers have been far less progressive in this area. The new US government under President Biden may prove supportive of improved stewardship and ESG in general. The US decision to sign up to the Paris Climate Agreement (again) certainly represents a change in tone from the top. And it is also possible that the SEC could introduce new disclosure requirements, similar to the UK – time will tell.

Sphere of influence

For investment companies, the challenge is not just to operate in a client-focused manner but to actively engage with and influence companies they invest in, thereby driving ESG and the broader responsible finance initiative.

This is not always easy. Investment management companies in high-growth, emerging markets such as India and China may incorporate good stewardship within their own business. For instance, Wells Fargo Asset Management (WFAM) have not only signed up to the UK and Japanese Stewardship Codes but also joined an investor initiative called Climate Action 100+ that aims to ensure the world’s largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters take necessary action on climate change. WFAM’s global equity asset base is predominantly US and emerging market-orientated and its annual stewardship report provides transparency around its proxy voting and engagement activities.

"Investment managers can include stewardship conditions before releasing any capital support"

The broad governance principles that determine which firms WFAM will invest in, stipulate that companies strive to maximise shareholder rights and representation; that boards are accountable to shareholders and should be responsive to them and that they address the sustainability of their business model and operations over the long term.

But one of the problems investors face (highlighted in a report from Schroders titled ESG and emerging markets investing) is that less stringent regulation has made it difficult to compare environmental or governance standards in emerging markets with those of developed market companies and even with each other.

For investors investing in these markets, acting as positive influencers (since they have a stake in the business) is frequently a challenge. Catherine points out that engagement is much harder in contexts where corporate management has no tradition of listening to minority shareholders. Guy Jubb, professor at the University of Edinburgh Business School, agrees that it is an uphill battle and that in places like Moscow or Beijing, progress is sluggish.

Echoing Catherine’s point, Guy says: "In places like India, Russia and China, you have individual people owning 40–50% stakes in large companies, so it can be very difficult for minority shareholders to get their voices heard. And you may have the situation where the stewardship in a market where fund managers want to invest in is not commensurate with their own guidelines."

However, Guy says, where institutional investors can exert influence with such companies is when these firms need to raise capital. Investment managers can include stewardship conditions before releasing any capital support.

"A lot more could be done globally with regards to stewardship of pension funds"

Colin agrees that opportunities for successful engagement with companies vary, and often this is geographical. But he insists there is quite a lot investment companies can do in emerging markets to encourage firms to adhere to international best practice.

He accepts that the lack of transparency in many emerging market businesses is often due to the culture whereby firms cater for local rather than international investors. Typically, these businesses are more opaque, which often deters foreign investor interest. However, he believes this only emphasises the need for investment firms to be clear in their messaging – specifically that emerging market companies will actively lower the cost of capital by being more open.

Colin also believes that the global move towards greater sustainability will itself prove persuasive. "We have seen some success already with the UN Principles for Responsible Investment."

Effective engagement between pension funds and members is another area of concern. "A lot more could be done globally with regards to stewardship of pension funds," Colin says. "Nevertheless, defined contribution pension models must improve member engagement, specifically using developments in technology to communicate to beneficiaries the decisions taken on their behalf and responding to feedback from members."

Catherine says pension funds play an important role in the private equity sphere too.

"There’s a huge need to raise standards of stewardship in private equity, hence the recommendations on this in the Asset Management Taskforce report. Pension funds that have been making bigger allocations to private equity can and should drive this change and insist on more stewardship by their private equity managers."

The bigger picture

Successful stewardship relies on large scale buy-in. There is a clear chain of benefits:

- Asset and investment managers listening to the individual investor (on whose behalf they are investing)

- Greater engagement between pension funds and members, enabling clear understanding of investment and stewardship objectives of beneficiaries

- Asset and investment managers being transparent in how and where they invest (indicating sector/asset class exposure and level of risk) and demonstrating how they actively influence companies they invest in to incorporate ESG best practice.

All these participants need to be involved. But, as we touched upon earlier, to create an economy-wide approach to stewardship, there needs to be input from a wider range of stakeholders such as government, regulators, index providers and investment consultants. In this way, better stewardship can ultimately offer benefits to the economy.

Guy believes these stakeholders play an important role in providing increased momentum to good stewardship. He argues that the development of ESG indices is positive because companies increasingly aspire to be included and, when necessary, will improve their ESG practices to achieve this.

"The impetus must come from everyone, not just institutional investors"

He also suggests that, while not in any way perfect, voluntary codes (not just compulsory regulations) can work, given the current momentum of ESG and responsible finance. He concedes that one of the downsides is that poor practice is not caught at an early enough stage, but believes the media, including social media, has a vital role in exposing poor ESG practices, as bad publicity (spread globally in seconds) has its persuasive powers.

This was dramatically illustrated when the The Sunday Times published allegations in July 2020 of unacceptable working conditions and underpayment of factory workers in Leicester, UK, who were making clothes for Boohoo, the online fashion retailer.

The allegations "sparked outrage across all media channels, and by politicians and investors alike and focused attention on broader governance issues," Guy says. "The share price collapsed by almost 50% as a number of leading investors dumped stock. The company launched an independent QC-led investigation. It found widespread evidence of unacceptable conditions and made a number of far-reaching recommendations, which the company is implementing, and the share price has recovered."

Finally, governments need to play their part too. Guy says that funded public service schemes, including local government pension schemes, could build stewardship into their investment processes.

If all stakeholders actively embrace good stewardship, the beneficial impact is much greater. Colin concludes: "The impetus must come from everyone, not just institutional investors. That way we can move the focus away from short-term profitability to long-term value."