In March 1952, American economist Dr Harry Markowitz forever changed the way the finance sector thought about investment through a

paper titled ‘Portfolio selection’, published in the

Journal of Finance. Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) set in stone the need to diversify assets. Defining risk as volatility, Markowitz argued that this was best managed by spreading investment across asset classes.

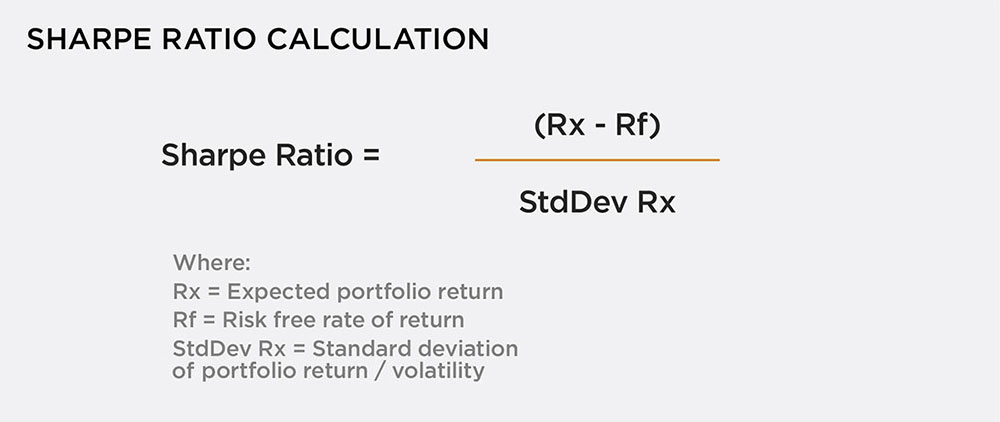

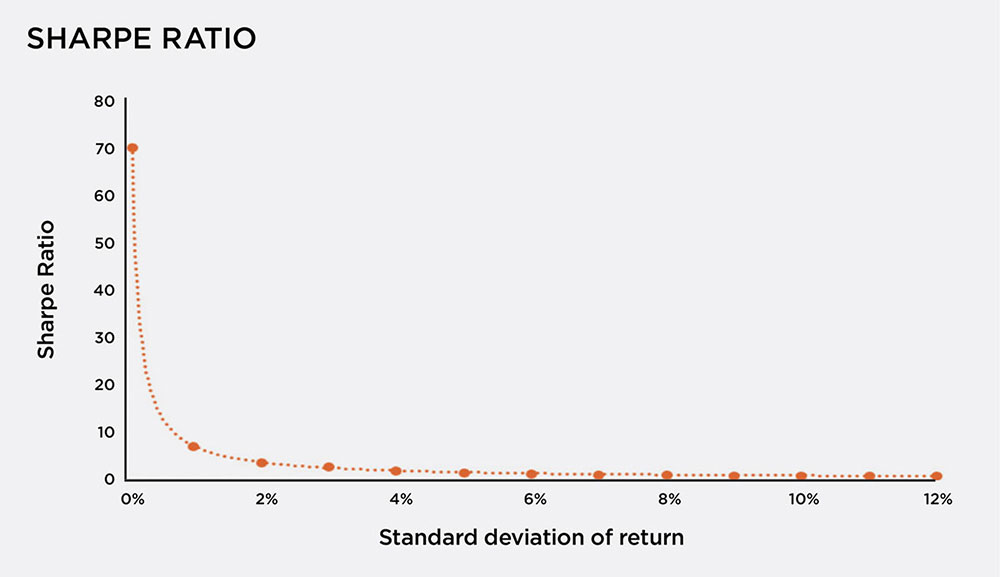

This allowed financial planners to mathematically measure risks associated with portfolios of assets – in units of standard deviations – and to assess the historical efficiency of a given portfolio via the widely used Sharpe ratio, which helps an investor understand the expected amount of return they might receive for the amount of risk taken to invest in that particular investment.

Source: Corporate Finance Institute

Using MPT, financial planners can create an ‘efficient frontier’ that is the point at which clients reach the highest possible return for the level of risk they are willing to take. The efficient frontier offers financial planners a clear and logical way to understand the ‘optimal’ assets to reward investors for appropriate amounts of risk.

Source: Corporate Finance Institute

MPT formed solid foundations on which investments have been made since 1952. Yet, financial theory cannot afford to rely on models from decades ago – no one would expect medicine or technology to have remained static for such a period of time.

By June 1991, in an article in the

Journal of Finance (register to read

here), Markowitz made clear that MPT was aimed more squarely at institutions rather than retail investors.

Doug Brodie CFP

TM Chartered MCSI, managing director at London-based Master Adviser, argues that sound as MPT is, it has been misapplied to individuals and was intended for open-ended, multimillion-dollar funds. Individuals, meanwhile, have more specific targets to achieve within a specified timeframe.

It is no surprise then that financial theories have evolved not only to incorporate new ways of thinking but to better cater to the investment experience of individuals as well as institutions.

Theoretical evolution

Academic Dr Paul Kaplan, director of research for Morningstar Canada, a Chicago-based global investment research and management firm, says that over time, understanding of risk has changed.

Critics of MPT argue that its definition of risk, its failure to accept extreme events, and an assumption that all investors are rational are key problems.

In response, Dr Frank Sortino, finance professor emeritus from San Francisco State University and director of the Pension Research Institute that he founded in 1981, began work on an alternative to MPT.

Dr Sortino created an asset allocation model that was bought by technology entrepreneurs Brian Rom and Kathleen Ferguson in 1988. Rom and Ferguson used Dr Sortino’s model to build portfolios that allocated as much importance to downside risk as to the potential upside. Describing this technique in the

Journal of Performance Measurement in 1993, Rom and Ferguson first coined the term Post-Modern Portfolio Theory (P-MPT).

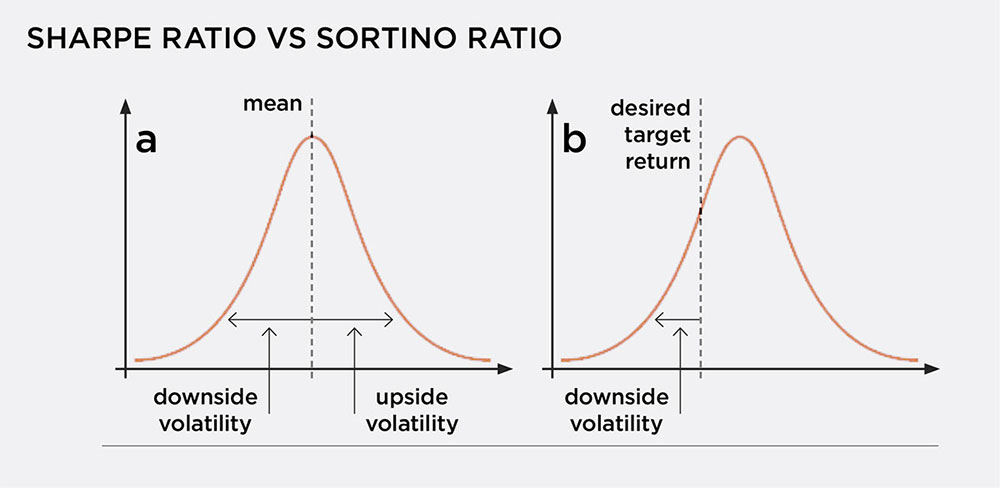

Dr Sortino had created an alternative to the Sharpe ratio. In his iteration, Dr Sortino penalises downside risk only when it falls below a level specified by an investor. The Sharpe ratio, meanwhile, treats ups and downs as equally relevant. The Sortino ratio was designed to replace MPT’s Sharpe ratio as a measure of risk-adjusted return and improved upon its ability to rank investment results.

Source: Sortino: A ‘Sharper’ ratio by Red Rock Capital. Sharpe ratio (left) measures return divided by (upside and downside) volatility, while the Sortino ratio (right) measures return divided by (downside) volatility only.

P-MPT argues that clients expect their investment to meet objectives and their biggest concern is a failure to do so. This is reflected in a 1993 article in the Journal of Investing (available to read here), where P-MPT proponents argue that MPT can be improved upon by better reflecting individuals’ understanding of risk. P-MPT says that loss matters more to retail investors than volatility.

Yariv Haim, investment manager at Sparrows Capital, says: “P-MPT takes a step beyond that one-dimensional measurement [of risk as standard deviation/volatility] by redefining risk as the possibility of underperforming relative to an investment objective.”

The risk within an asset class, according to P-MPT, is associated both with its volatility and its likelihood of failing to achieve a minimum acceptable return. As a result, the efficiency of an asset class within a portfolio varies depending on the individual financial objective of the clients.

P-MPT also tackles MPT’s failure to appreciate the likelihood of extreme events. MPT relies heavily on the simplifying assumption that asset returns are normally distributed in a ‘bell-shaped curve’, which can be described by its mean and its variance or standard deviation. Put simply, MPT uses a mathematical equation to measure the risk of various assets, using standard deviation to assess the extent it will differ from the mean risk return.

Yariv says: “Real world evidence shows that extreme events occur much more frequently than what would be suggested by the normal distribution. Actual distributions often present ‘fat tails’ – extreme events – that should be taken into account in any measurement of risk.” Clients will recall the last extreme event when the markets went into freefall during the 2008 financial crash.

"Real world evidence shows that extreme events occur much more frequently than what would be suggested by the normal distribution"

To understand the difference between how MPT and P-MPT view risk, cash is a helpful example. Under MPT, cash is a low-risk asset to include in a diversified portfolio since it experiences very little volatility. However, under P-MPT the client’s objective, perhaps generating 8% net per annum to fund their retirement, would be considered. In this case cash is incredibly risky since – under current economic conditions – including only this asset class would reduce the client’s chance of reaching their goal.

Yariv says: “The efficiency of an asset class within a portfolio varies depending on the individual financial objective of the client.”

P-MPT also tackles the assumption that all investors are rational. In 1991, the emergence of

Prospect Theory – a strand of behavioural science – fed into P-MPT and gave greater clarity about how investors’ attitudes can overrule rational decision-making. Founded by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, Prospect Theory says humans prefer certainty and give less credence to probable outcomes. This suggests that when presented with a 50% chance of receiving £100 or a 95% chance of receiving £50, the individual will take the more certain but lesser amount.

Yariv says: “They found asymmetry in our appetite for risk versus our desire to outperform: fear is more powerful than greed.”

Practical application

P-MPT has encouraged financial planners to think about different scenarios and to model possible events and the impact on client portfolios. This has the potential to improve communication between planner and client, which Yariv says helps clients to stay on track to achieve their long-term investment objectives; particularly important in times of market uncertainty.

Financial planners might also benefit from understanding P-MPT when tackling more recent investment styles such as factor investing. Factor investing – sometimes known as smart beta – applies an element of active investment to traditional passive strategies that goes beyond the foundations of MPT.

Rather than using capitalisation-weighted indices, investors or institutions create a database of securities based on volatility, size, value and momentum.

Yariv says: “Factor investing can be seen as a subset of P-MPT, which exploits historical risk/reward anomalies explained by herd investor behaviour. The incorporation of factor tilts into portfolio design is a practical step to improve client outcomes.”

Following the herd

The herd mentality – copying the behaviour of others – is strong in the investment world. The fear of missing out on potential returns or seeing their money disappear often drives investors to buy the same assets at the same time. Examples include panic selling in a bear market or ploughing money into a bull market. The herd mentality can create ‘bubbles’ where money pours into assets that are not sustainable and they burst, causing potential serious losses. Despite the rise of P-MPT as an alternative to Markowitz’s original theory, many financial planners still rely on MPT to guide investors.

Jonathan Gibson CFP

TM Chartered MCSI, managing director at Wells Gibson, says his firm remains confident that the approach based on MPT “will provide clients with every chance of having a successful investment experience”.

He adds: “By owning a well-diversified portfolio for all seasons, having faith in capitalism, allowing the markets to do the heavy lifting, being patient and remaining disciplined, clients give themselves – with our continued help and guidance – every chance of success.”

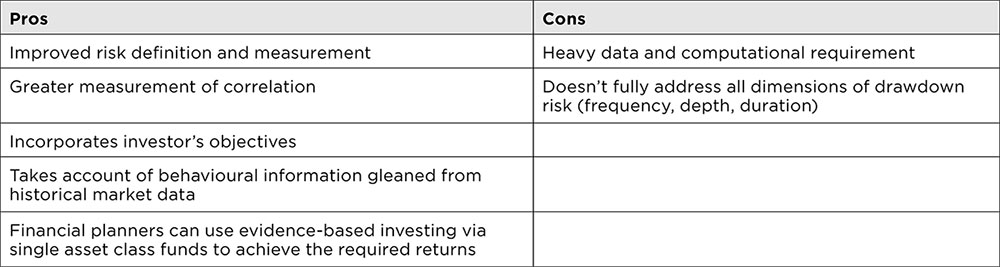

Jonathan says that P-MPT can be complex and unwieldy. Yariv adds: “The data and computational power required to produce a robust P–MTP portfolio are substantial and out of reach of most financial planners.” But there are other options.

Alternative school of thought

P-MPT is almost 30 years old and has been followed by new iterations and evolutions. In 1993, Professors Eugene Fama and Kenneth French created a theory advancing P-MPT and building on the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). This was called the Fama-French Three-Factor Model.

CAPM is widely used by proponents of MPT who argue that the higher the share’s volatility, the lower the price. It is focused solely on market risk and says the higher the risk, the more reward for investors. The Fama-French Three-Factor Model argues that CAPM oversimplifies the relationship between risk and reward for equity market investors

Fama and French said that there are other factors, namely size and value, that also influence share price. They said small companies tend to outperform larger ones and that value stocks generate higher returns, arguing that three factors influence asset prices rather than just one. In 2015, Fama and French went on to create the Fama-French Five-Factor Model, which added profitability and investment to the previous three factors.

Other theories continue to emerge, building on Markowitz’s seminal work. In 2017, Morningstar’s Dr Paul Kaplan published a paper in the Journal of Investing called ‘From Markowitz 1.0 to Markowitz 2.0 with a detour to Post-Modern Portfolio Theory and back’. In this article, Paul discusses the development of portfolio theory, from Markowitz’s original work up through the approach that he and Stanford Professor Sam Savage developed that they call Markowitz 2.0.

Paul says that P-MPT added little to the development of portfolio theory because Markowitz himself had already introduced its main ideas back in 1959, but with a much better implementation. Paul points out that P-MPT fails to adequately model fat tails, which have a large impact on downside risk.

“P-MPT is completely subsumed by Markowitz 2.0, 2010,” he tells

The Review. “There are any number of ways of measuring risk and return, but Savage and I introduced a methodology that was general enough so that we could model just about any return distribution, including those with fat tails.”

Paul says Markowitz 2.0 goes beyond MPT and P-MPT in more effectively modelling fat tails and taking into account long-term investment objectives. However, he adds that, like MPT, Markowitz 2.0 is better suited to institutional rather than retail investors.

As Doug from Master Adviser says, the person in the street does not care about theory; they care about protecting what they have.

“If a client is targeting income, it is our job to meet that target and not worry about theory,” Doug says. He adds that Markowitz himself invested his own money by dividing it equally between equities and bonds, therefore ignoring his own theory and that of anyone else.

Theories will continue to evolve; existing ideas will be debunked and debates will rage. Clients, meanwhile, will want to ensure that they can achieve their financial and lifestyle objectives without taking undue risks.

The pros and cons of P-MPT

Seen a blog, news story or discussion online that you think might interest CISI members? Email bethan.rees@wardour.co.uk.