In the first of this two-part article, we looked at the 'tone from the top', whistleblowing (or ‘speak up’) policies and compliance versus ethics – all different elements that can inform how culture is created, managed and measured. However, the culture of an organisation is difficult to assess. Websites such as Glassdoor go some way to give investors a glimpse of what life is really like inside certain companies, but generally it is hard for investors to properly assess the ethical nature of any given business.

Talk to most governance experts and they’ll admit that although investment professionals are becoming more aware of social and ethical issues – with tax and offshore entities a real concern – most attention has tended to focus on what one might refer to as more ‘mainstream’ CSR measures, such as philanthropy and environmentally friendly initiatives. But even here progress has been limited.

Paying lip service As Grant Thornton’s report Trust and integrity – loud and clear? discovered, only 46% of companies have CSR policies integrated into their business models, prompting the firm to describe their implementation of CSR as “paying lip service”.

88%

The proportion of cases whereby solid environmental, social and governance practices result in better operational performance of firms

Many large corporates may not be taking their CSR governance seriously, but many of their biggest institutional investors certainly are. Morgan Stanley, for instance, has set up its own institute to examine the wider issues around sustainability generally. According to Jessica Alsford, Head of Morgan Stanley’s Sustainable and Responsible (S+R) equity research group, the bank is now making extensive use of quantitative measures that look at the long-term viability of a business model. “It’s not enough anymore just to be a good corporate citizen. Increasing numbers of asset managers want to know that a company is managing the risks and seizing the opportunities arising from environmental and social changes, in a way that drives shareholder value,” says Alsford.

London-based Arabesque Partners is another institutional investor looking for hard numbers to measure corporate governance and sustainability – measures it hopes will make it a better investor. According to CEO Omar Selim: “Arabesque is not using environmental, social and governance (ESG) data merely to please ethical investors at the expense of performance. We use ESG information to generate outperformance. We are suitable for all global investors, not just ESG investors.”

The firm also recently ran research with the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford, which looked at sustainability via a meta-analysis of 200 academic studies. This report found that 90% of the studies on the cost of capital show that sound sustainability standards lower the cost of capital of companies, while 88% of the research shows that solid ESG practices result in better operational performance of firms. Crucially, 80% of the studies “show that stock price performance of companies is positively influenced by good sustainability practices”.

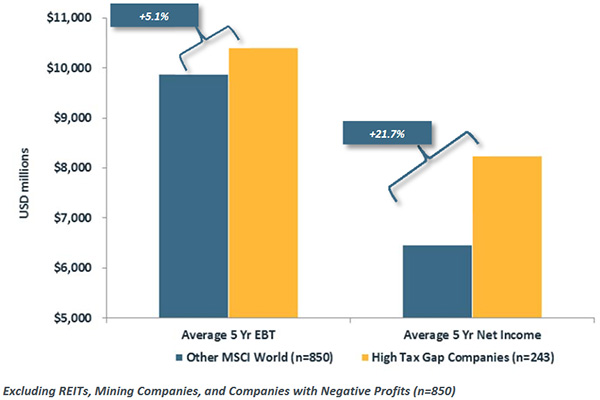

Growing interest in sustainabilityQuantitative driven approaches pioneered by the likes of Arabesque Partners and Morgan Stanley are becoming more important in part because end users – ordinary investors – are growing more interested in issues of sustainability. But what happens when this same investor base starts demanding action about corporate tax and offshore policy post Panama? In 2015, for example, the index firm MSCI released its Re-examining the tax gap report, which looked at the taxation of the leading businesses in the MSCI World Index. The firm’s researchers found that taxes paid by the 243 companies in the index with the largest tax gaps (defined as the difference between the reported tax rate paid and the tax rate of where companies generate revenues) would have totaled an estimated $82bn per year in taxes had these companies been paying taxes at the same rate as their peers in the index. (The companies’ combined actual paid tax is not reported in the MSCI survey.) This massive corporate tax gap is now the subject of intense multinational scrutiny – the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is currently designing new policies on transfer pricing and country-by-country reporting.

Comparison of earnings before tax and net income between high tax gap firms and other MSCI World Index companies, 2009–2013

Source: MSCI

Source: MSCI

According to Fiona Reynolds of the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), a UN-backed body championing better investment governance: “Responsible investors and well-run companies will acknowledge that tax is not simply a cost to be minimised, but a vital investment in the local infrastructure, employee base and communities in which they operate.”

A recent report by her organisation called Engagement guidance on corporate tax responsibility mapped out a series of due diligence steps for investors worried about opaque tax and company domicile policies (see boxout). This analysis started out by stating: “Certain sectors have developed a reputation for aggressive tax planning, as they are more exposed to scrutiny (for example, consumer goods), or are well placed to employ different strategies (for example, intellectual property rights at pharmaceuticals). Aspects of recent or upcoming legislation may be more pertinent to some sectors (for example, a focus on technology though [the OECD’s] Base Erosion and Profit Sharing, obstacles to mergers and acquisitions activity by pharmaceuticals).”

Implementing due diligenceThe report also features advice on due diligence for corporate tax avoidance from Steven Bryce, of Singapore-based investor Arisaig Partners (Asia). His firm selects companies in three stages:

- Stage one uses company reports and other data to find out the weighted effective tax rate and how much this deviates from the actual rates.

- Stage two looks broadly at what sort of tax policies these companies have.

- Stage three examines publicly reported cases of inappropriate tax practices within their portfolio companies.

Nordea Group, one of the largest financial services firms in the Nordic and Baltic region, also detailed its attitude towards tax governance in its own white paper on the subject published in 2014. It says it favours proactive companies that have “integrated aspects such as stakeholder opinion, brand implications and reputational risks as part of the tax planning decision process".

The report goes on: "An aspect that these companies consider is, for example, how a specific tax structure would be perceived by external stakeholders, such as media and non-government organisations. We favour companies that have a responsible tax policy that is approved by its board. Companies should also have a tax strategy that explicitly considers brand and reputational risks.”

But perhaps the simplest and best advice comes from the Institute of Business Ethics’s Philippa Foster Back. She suggests that investors ask to see the business’s tax policy and then see how it marries with the broader values of how it does business: “If [it’s] on record as championing transparency but the policy on tax isn’t transparent, there’s likely to be an issue.” If the Panama Papers have taught us anything, it’s that we all live in a new age of transparency, with business ethics the new corporate frontline.

Tax due diligence checklist for investors

In its report on corporate tax responsibility, the UN-backed governance organisation Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) helpfully suggested a simple set of guideline policy areas and questions for those investors wanting to run due diligence on a corporate’s tax structure. The PRI suggests focusing on six core areas:

1. Tax policy

Check if the company has a comprehensive tax policy publicly available.

Ask if the company has considered publishing a tax policy/principles to indicate its approach towards taxation.

2. Tax governance

Check whether the company provides disclosure on clear board level oversight of tax strategy.

Ask if tax is formally a part of the risk oversight mandate of the board, and how often and for what reason tax is discussed at board/committee level.

3. Managing tax-related risk

Check whether the company discloses any information on tax-related risks and how they are managed, including any discussion on pending investigations of tax positions.

Ask how the company defines and manages tax-related risks, and what its top three tax-related risks are.

4. The effective tax rate

Check the company’s global effective tax rate and if the origin of any significant difference versus its weighted-average statutory tax rate is explained in detail.

Ask what drives the gap between the company's effective tax rate and its weighted-average statutory rate based on its geographic sales mix.

5. Tax planning strategies

Ask to what extent the company's profit after tax relies on its presence in tax havens or incentives and structures that enable very low taxation (for example, <15%) of profits.

6. Country-by-country reporting

Ask how the company is preparing for country-by-country reporting.