Banks and financial institutions based in the UK have been on the receiving end of an onslaught of financial penalties over the past ten years, imposed by regulators seeking to punish them for a range of offences.

Show me the moneySince the onset of the global financial crisis in late 2007, the FCA and its predecessor, the FSA, have handed down a total of £3.6bn in fines. Many of these were imposed on British banks and financial institutions, but the regulators also exercised their power to hand down penalties to foreign-owned banks operating in London.

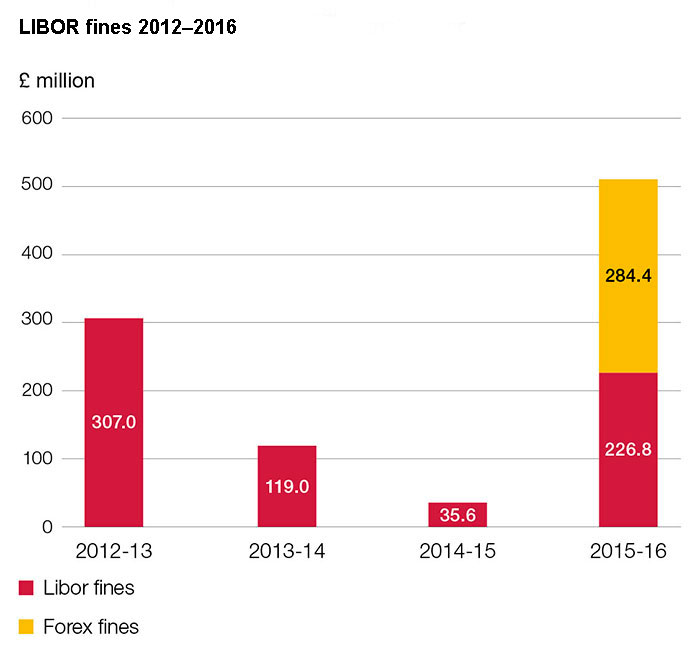

One of the biggest chunks related to £688m of fines imposed on UK banks for their role in fixing the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) (see graph below). Regulators found several banks in the US and the EU, including the UK, had manipulated LIBOR for profit.

Source:

Investigation into the management of the LIBOR Fund

Banks have been fined for other offences too, including manipulation of foreign exchange markets, precious metals rates and the ISDAfix rate, now known as the ICE Swap Rate, that helps determine the value of interest-rate swaps, securitised bonds and options on swap contracts. On top of that bill has come fines relating to the payment protection insurance (PPI) misselling scandal, money laundering violations and failures in handling client money. Of course, the total financial cost to banks is much higher as they have been subject to fines by other regulators.

Analysis in August 2017 by the Conduct Costs Project Research Foundation shows the level of fines, customer compensation and other costs resulting from bank misconduct, racked up by 20 of the world’s biggest banks over the five years to the end of 2016, amount to £264bn (inclusive of provisions). The bill for what it calls ‘conduct costs’ represents an increase of 32% when compared with the previous five-year period.

The foundation, a social enterprise, has worked to codify costs to make clearer what are fines as opposed to other costs paid by banks, and to trace conduct costs from cause to consequence. “The cost codes stress the fact that the consequences of misconduct are not just a matter of fines and/or penalties,” Chris Stears, its research director, says.

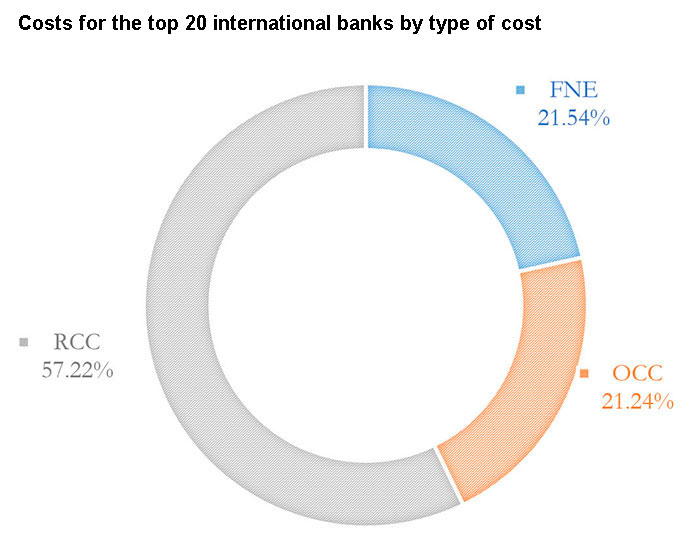

The foundation’s analysis shows that while a fifth of costs (21.5%) relate to fines, the remainder relates to other conduct costs (see chart below). For the five UK banks, fines make up 13.9% of the total costs bill.

Key

FNE: Fines and/or penalties imposed by a regulatory and/or other ‘conduct’ authority.

RCC: Conduct costs that arise out of a regulatory directed redress, whether or not it results in formal proceedings, fines or penalties (other than FNE).

OCC: All other costs.

Source:

Conduct costs project report 2017

Follow the moneyUp until 2013, the FCA had kept all income from fines and used it to subsidise the cost of fees to the banks; until then-chancellor George Osborne announced that fines paid by banks and others who broke the rules would go to the “benefit of the public and not to other banks”.

Since then, the FCA has transferred approximately £2.9bn to the Government, according to a Treasury spokesman. By convention, all revenues go into a central account and become part of monies allocated to government departments in the Budget. This makes it hard to identify where the money has gone. However, there are some clues from one-off announcements by government ministers.

In December 2014, Osborne used the Autumn Statement to announce that £1.2bn – or more than a third of the total – would be invested in GP services using fines for misconduct on the foreign exchange markets.

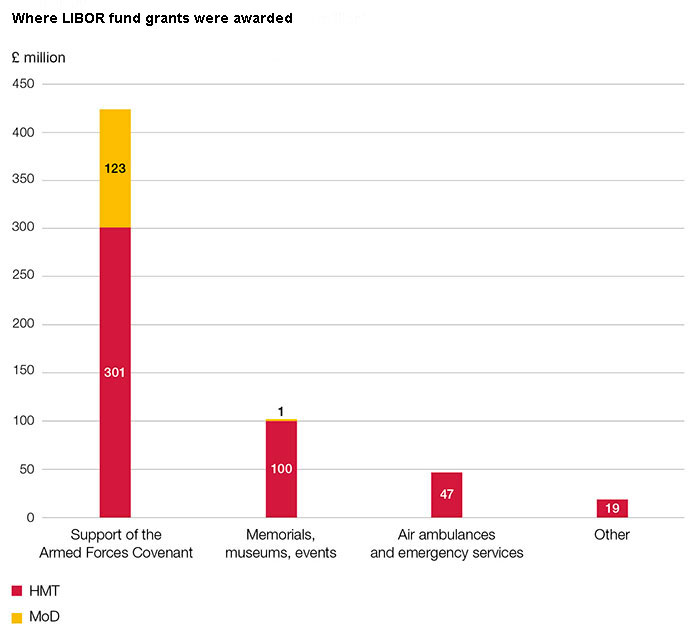

The £688m fine related to LIBOR manipulation was put into a fund that was topped up in 2015 with a £284m penalty against Barclays for foreign exchange manipulation, making a total of £973m. The majority of this has been to support armed forces and emergency services charities and other related causes (see graph below), according to an

investigation published in September 2017 by the National Audit Office (NAO), the financial watchdog of the Government.

Source:

Investigation into the management of the LIBOR Fund

The biggest single payment was £200m, pledged in April 2015 by then-Prime Minister David Cameron, to support 50,000 apprenticeships for unemployed 22- to 24-year-olds. Of the remainder, 729 different grants have been awarded to 639 different charities and causes. Grants ranged from £1,000 to £50m. The average grant was £800,000.

The biggest bank fines in history

The largest fines were all imposed by US regulators, mainly over the securitisation of toxic mortgage assets. A majority of the money has gone directly towards programmes designed to help homeowners and borrowers. The unlucky seven are:

1. Bank of America, 2014: $16.65bn for dealing with mortgage backed securities that were not financially sound, leading up to the sub-prime mortgage crisis.

2. JP Morgan Chase, 2013: $13bn to pay for Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual’s actions in the run-up to the financial crisis.

3. Bank of America, 2012: $11.8bn contribution towards the US’ National Mortgage Settlement, setup after the sub-prime mortgage crisis.

4. BNP Paribas, 2015: $8.9bn for violating the International Emergency Economic Powers Act and the Trading with the Enemy Act.

5. Bank of America, 2011: $8.5bn to pay for Countrywide’s sub-prime mortgages.

6. Deutsche Bank, 2016: $7.2bn for selling toxic leads in the build up to the sub-prime mortgage crisis.

7. Wells Fargo, 2012: $5.4bn contribution towards the US’ National Mortgage Settlement, setup after the sub-prime mortgage crisis.

Of the £592m distributed through grants, two-thirds were in response to direct requests for money, while the remaining £207m was allocated through competitive application processes.

Meanwhile, £141m had still not been dispersed. The NAO also said that the Treasury “did not have a formal comparative assessment process for awarding the majority of the grants” from the fund.

In a critical verdict, the NAO concluded that the Treasury and the Ministry of Defence were not able to confirm that charities spent all grants as intended. “The Government cannot yet demonstrate the impact the LIBOR grant fund has had as it has not been evaluating the impact of the grant schemes on the charity sector.”

The NAO also concluded that it had not been possible to distinguish the impact of the £200m LIBOR fund spending on apprenticeships from the performance of the overall scheme. This still leaves some £1bn unaccounted for.

While most people are likely to support grants to armed services charities and other good causes, it is not the case that the money went back into the pockets of the people affected, directly or indirectly, by financial misfeasance.

Marco Meyer, a researcher in the Trusting Banks Programme at Cambridge University, says money raised from bank fines should be used on related spending. “An obvious way is to put more resources into regulation, building capability at the bank, and the FCA, to put them in a position to work on a par with banks.”

James Daley, founder of campaign group Fairer Finance, agrees that fines would be best used to improve standards in that sector and put measures in place to prevent malpractice happening again.

He warned that a lack of transparency over how the money was used could undermine confidence in the regulation system. “They get away with it being a grey area at the moment. They should not just be pocketed by the Treasury to use on whatever they choose. There should be a clear link between those fines and a good cause.”

In times gone by, fine money was used to offset the cost of regulation. The ‘goodies’ paid less for complying with the rules, while the ‘baddies’ paid for their misdeeds by contributing a bigger slice towards financial services’ regulation. Broader questions are raised now this is no longer the case.

Currently, fine money is being used as a means of government expenditure. Is it right that the government is being financially propped up in this way?

An alternative could be to boost compensation funds. How else could it be spent? In any event, more accountability and visibility of the government’s spend is needed.

Seen a blog, news story or discussion online that you think might interest CISI members? Email jake.matthews@wardour.co.uk.