The current low cost of buying exchange-traded funds has seen their popularity grow across Europe. Rachel Revesz, Senior Staff Writer at ETF.com, looks at how the funds work, and explains what benefits and risks they bring to investors

With over 1,400 exchange-traded funds (ETFs) listed across Europe today, and most of them trading actively on the London Stock Exchange, these passive and rules-based vehicles can make up a valid part of any investor’s portfolio. Whether you are looking for sterling-denominated gilts, European ex-UK banks, high-yield euro-denominated bonds, Chinese money market instruments or even robot-makers, ETFs can offer investors a transparent and low-cost way to get that exposure. A total of 246 ETFs launched in Europe last year alone, ensuring a steady flow of new products to choose from.

All ETFs – minus a handful of so-called ‘active ETFs’ – function in the same way. They replicate a rules-based index and the ETF aims to return the same performance of the index to the investor, minus fees. The ETF manager’s job is to ensure there is as little tracking deviation as possible, which either comes in the form of tracking difference (difference in returns from an ETF and its index) or tracking error (the volatility of the ETF’s deviation from the index).

Other funds face challenge

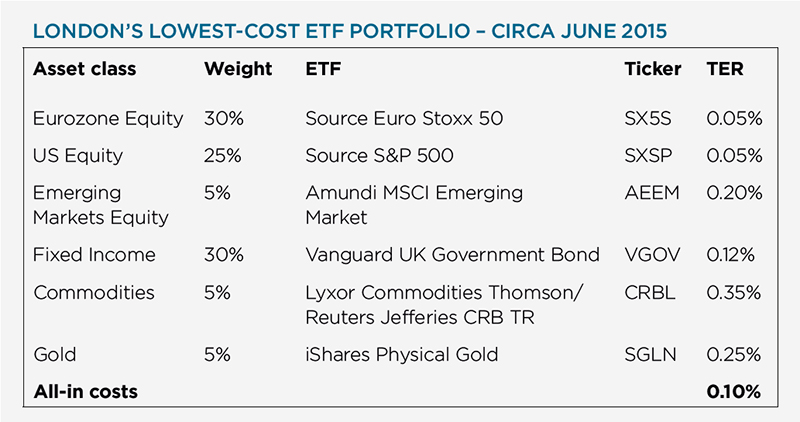

Recent data from Lipper at Thomson Reuters shows that the average annual fee for an ETF registered for sale in the UK is just 0.38%, as opposed to 1.22% for the average actively managed fund. ETFs are democratising investment: everyone from a pension fund to a man on the street can buy an ETF for the price of just one share (see the boxout as to how you could put together a multi-asset portfolio of ETFs for just 0.10% per year).

As a result of these low costs, popularity is growing: ETF assets listed in Europe have risen exponentially from just €5.8bn in 2001 to close to €450bn as of July this year, according to Deutsche Bank.

How to trade ETFs

When it comes to taking that first step, investing in an ETF is slightly different to a traditional active mutual fund. Say you and three others have £10,000 and you invest it into an ETF. You receive 100 shares, worth £100 each. The ETF manager then goes into the market and buys £40,000 worth of stocks. If he doubles the money to £80,000, then your shares are now worth £200. But it also works in reverse – if the manager loses half your money, your shares will plummet to £50. And every time a new investor buys shares in the ETF, the manager uses their money to buy more stock.

In the background are the authorised participants, or market makers, whose job it is to swap securities for ETF units. If your ETF price rises to a premium or falls to a discount to fair value of the ETF’s holdings, authorised participants can arbitrage away the difference, meaning your ETF is unlikely to move significantly away from fair value for any extended period.

In this regard, although they trade on exchange, investment trusts are different to ETFs in that they often rocket to wild discounts and premiums, based solely on supply and demand.

ETFs, however, can also simply rely on supply and demand at their most basic level. When Athens shut down its stock exchange in June, the Greek equity ETF from Lyxor, listed in Stuttgart, continued to trade. Investors were therefore speculating on the equities’ value while the underlying market was closed, and that can lead to significant premiums and discounts in the ETF, without the neutralising force of market makers quoting real prices.

ETFs trading while the market is closed also took place in Egypt in 2011, during the 1997 Asian crisis and, more recently, in China, with many underlying companies closed for trading. ETFs therefore can be used as useful tools for price discovery, as long as the stock exchange where the fund is listed allows it to continue to trade. Another point on premiums and discounts is if, say, a Europe-based investor buys an ETF tracking Chinese equities, the ETF can move away from fair value if it trades while the domestic market is closed – on a different time zone – or during a public holiday.

No free lunch

While there might be many benefits to considering an ETF, there is no such thing as a free lunch and investors should be aware of the risks. For example, mutual fund holders would not have experienced a fluctuation during a flash crash, yet ETFs on an exchange would have seen their value plummet in the blink of an eye.

And that is not the only risk out there: there are also trading costs. These can be expensive and eat into your profits, and they tend to be hidden in the small print. The average cost to trade an ETF on an advisory fund platform is around £12, from brokers like Winterflood Securities. But there are ways to lower costs if you can shop around. If you are buying a small number of ETF shares and selling them shortly thereafter, the commissions can eat up any savings from the expense ratio versus a mutual fund – not a good tactic for pound-cost averaging.

Understanding the spread

The third risk you cannot avoid is the bid/ask spread. If you are saving 20 basis points on an expense ratio but paying 30 basis points in spreads on a round-trip trade, your total cost for a one-year holding period is higher in the ETF than it is in a competing mutual fund. ETFs are ultimately cheap, transparent and democratic investment tools that access almost any market an investor could wish for. It is time for investors to understand their benefits, as well as their risks, and to consider ETFs as an increasingly important part of the investment universe.

The original version of this article was published in the September 2015 print edition of the Review.