While fintech may seem a recent phenomenon, it has been evolving over decades and has adapted to the various economic crises, bubbles and waves of invention. The pace of advancement and level of customer deployment has been varied and driven by factors such as seizing market share, generating profitable growth and disintermediation. More recently, regulatory requirements and customer appetite for connectivity and mobility have shaped fintech innovation.

With financial markets still bereft of their own industrial revolution, the latest developments in fintech are pushing the boundaries of technological advancement in finance. They have enabled inventions such as crowdfunding, virtual currencies and mobile payments, which have redefined our expectations in terms of scale and what’s achievable.

Many major liquidity contributors, regulators, central bankers and market infrastructure providers are now looking to embrace, adapt and adopt new fintech opportunities: for example, blockchains and distributed ledgers – and their successors – which offer the opportunity for T-instant clearing and settlement (see boxout for definitions). Such advancements are not without risk, but could significantly reduce post-trade costs and release large amounts of high quality collateral currently pledged to offset transaction exposures.

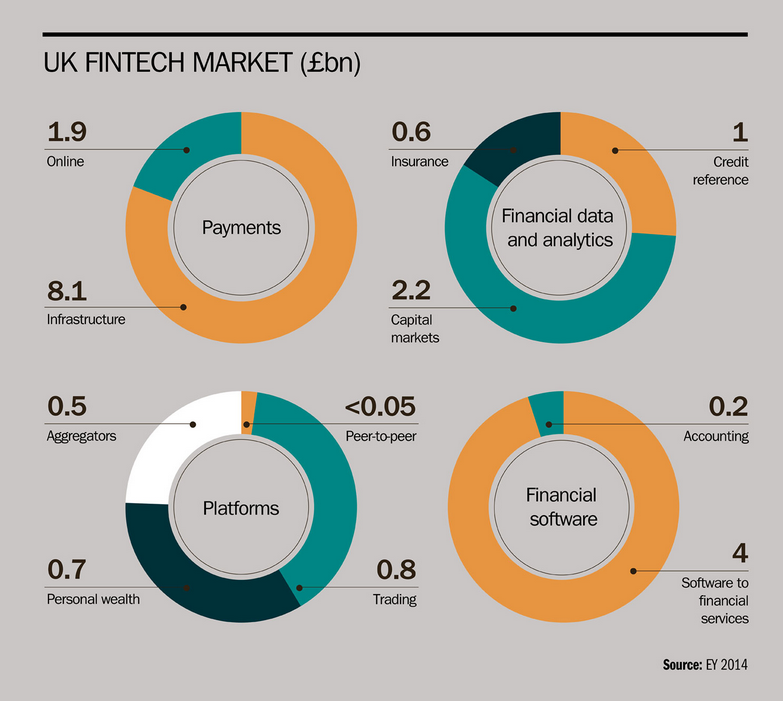

Space for innovationThe UK is Europe’s leading centre for fintech innovation. The industry was worth £20bn in 2014, with £342m of investment pumped into the sector during the year. Investment in fintech has grown more quickly in London than anywhere else, with average annual growth of 74%. Further north, CodeBase in Edinburgh has been crowned the largest technology incubator in the UK and one of the fastest growing in Europe, nurturing some 60 companies and driving investment in tech start-ups.

The UK Government is now making fintech a priority, and aims to create 100,000 new jobs in the sector by 2020. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, expressed his pro-fintech stance at the Bank of England’s Open Forum in November. “London is good at both ‘fin’ and ‘tech’,” he proclaimed, before saying that British regulators would provide “the space where innovation can happen”.

74%

The average annual growth of investment in London's fintech sectorSo influential are some innovations expected to be, that 33% of Millennials (those aged under 35 who have grown up with technology) do not think they will need a bank in five years’ time, and prefer instead to use these newer and alternative methods of savings, transfers and loans instead, according to

research by Goldman Sachs.

Nicolas Cary, co-founder of crypto services provider Blockchain, echoed this point at the recent MoneyConf in Belfast. “I am a millennial,” he said. “I can tell you that I do not expect to have a bank account soon. I already use Bitcoin for everything. All the employees in my company are paid in Bitcoin. It takes just minutes to process a payroll for our entire team. It is the future.”

On the fringesBut Bitcoin, it is argued, sits aside from the benefits that blockchain and distributed ledger technology have the potential to yield. Bitcoin adoption has gained a certain reputation on the basis of its murky origins in the darknet marketplace of Silk Road and its elusive creator Satoshi Nakamoto, who

may not even be a real person. But cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are

beginning to shake off their bad raps, and many large banks, including Santander and Deutsche Bank, have been testing these and other technologies through innovation hubs. “Some challenger banks, such as Fidor, have gone further by setting up open banking platforms through application programming interfaces, on which other fintech companies are providing additional services,” Lisa Moyle, Head of the Financial Services and Payments Services Programme at techUK, told

the Review.

“Financial institutions have been working in the same way for the past 40 years, so they think, ‘why should we change?’”For now, however, smaller start-ups are the main inhabitants of the fintech space. Matteo Rizzi, General Partner at SBT Venture Capital in Brussels, says: “It is fringe business – not really core – where we are seeing the technology used most.

“The core financial institutions have been working in the same way for the past 40 years, so they think, ‘why should we change?’” he adds. “But if you want to adapt to the way in which people are saving and using banking technology, all mobile, all ubiquitous ... I think it will slowly move into the core, but regulators have not yet figured out the best way for it to function.”

33%

The proportion of Millennials who do not think they will need a bank in five years’ timeSome experts believe that established, older institutions are simply weighed down by too much bureaucracy and will be slow to act, while start-ups are more nimble and open to new ideas.

“Fintech start-ups can work directly with large corporates on select needs and allow companies to bypass banks,” says Mohit Mehrotra, Executive Director of Consulting in Southeast Asia at Deloitte. “The key here is the pace of delivering efficient and innovative solutions that manage the risks of clients as [they] rapidly evolve to meet the changing needs of their end-client in the new digital economy,” he adds.

Golden recordsOne of the attractions of fintech is the element of transparency it provides. Blockchains, for example, provide a ‘golden record’ about every bitcoin transaction taking place within the chain that can be referenced by all market participants. This significantly reduces the number of failed transactions.

London-based start-up Everledger, for example, uses the blockchain golden record, although ‘diamond record’ may be more apt. The firm offers a global distributed ledger that tracks diamonds via dozens of data points associated with each stone that can be cross-referenced to combat diamond fraud and theft. Everledger’s founder and CEO Leanne Kemp said that prior to such innovation, the global financial services industry was “being strangled by a lack of transparency”. In July 2015, Barclays chose the start-up to be a part of its fintech ‘Accelerator’ programme.

Another appeal of fintech is the potential for instant, or same-day, transactions, often referred to as T-instant or T+0. Traditional T+3 (transaction trade date plus three working days) settlement can be a pain for dealmakers. Not only are there the high costs associated with post-trade processing, there are also concerns over the transfer actually taking place and the right people receiving the right amount at the right time. T+3 has been reduced throughout Europe to T+2, a step in the direction of faster payments. But distributed ledgers stand to remove the processing period almost completely by placing a digital currency in a decentralised payment system. In a move mooted by some experts, the digital currency within the system could include central bank money – a fairly radical and progressive development.

Financial institutions have wanted to achieve T-instant for a while but have not been able to for several reasons. As Rizzi points out: “The way that the banks have been adapting so far is to build more layers and processes on top of the existing infrastructure. So, core banking systems have not adapted to real-time transactions. If they want to compete, they will have to look at their systems and build from the ground up.”

Shifting the trustFintech makes the clearing process more efficient – transactions within the same trading day, rather than a day or two later, are now a serious proposition. Others argue that this streamlined approach does not allow for enough checks and processes behind the scenes. Instead of banks being trusted to hold and check the validity of the digital record, digital currencies utilise a publicly available ledger containing the record of every transaction by every user. While this provides transparency as outlined above, it means that reliance shifts from well-established institutions to the robustness of the network and the rules established to change the ledger.

There is also the issue of regulation. While banks are subject to reams of regulatory requirements – the newer among them include ‘know your customer’ and revised anti-money laundering laws – distributed ledgers rely on local independent operators that do not fall within the strict remit of banking regulation. These operators must take steps themselves to adhere to regulations. However, there is a safeguard in place in the form of ‘permissioned’ blockchains, whereby the market participants’ identities can be easily obtained by regulators and auditors if deemed necessary.

All this being said, the fact that many countries are working towards real-time same-day settlement schemes will only add to their use gaining credibility. Singapore is currently in the final stages of testing its almost real-time payments system, while Australia, the Netherlands and Poland are all placing much faster payment settlement as a top fiscal priority. What will be interesting to see is how fintech startups handle the difficulties posed by the full implementation of the European markets directive, MiFID II. This directive has created its own headaches, particularly in the area of execution transparency. Most serious players expect many firms – and markets – to fail to meet the deadlines for this project, which challenges even the most sophisticated financial technologies.

With markets still feeling the effects of the 2008 financial crash, it is understandable why the financial services sector may be reluctant to take on new tools for financing without fully understanding the implications and risks. But Accenture posits that by 2020, 30% of banks’ revenues could be lost to these new players that, granted, may have less clout, but benefit from greater agility. If the stats are true, financial institutions should be getting on board – and sooner rather than later.

The estimated market split in the UK fintech sector in 2014, according to EY

The estimated market split in the UK fintech sector in 2014, according to EY

Fintech jargon buster

|

| Application programming interfaces |

A collection of rules, protocols and routines for building software applications. They can be thought of as a sort of contract from one piece of computer software to another.

|

| Bitcoin |

A digital payment network that uses open source technology to operate without the need for a central authority or bank. Bitcoins are used as the currency, or cryptocurrency, within the network.

|

| Blockchain |

A continuously growing digital database, a chain of ‘blocks’, with each block representing a transaction record. The most widely known application of blockchains is recording Bitcoin use.

|

| Distributed ledger |

Essentially, a digital record of who owns what. Bitcoin is a distributed ledger, as its records are held in a blockchain.

|

| T-instant |

A same-day settlement scheme, meaning that payments can be made the same day rather than in one (T+1) or two (T+2).

|