When London’s junior stock market AIM opened its doors 21 years ago, it was home to just ten listed companies with a combined market capitalisation of £82m. It has come a long way since then. By the end of March this year, those figures had risen to 1,020 and £71bn respectively.

Overall, more than 3,600 companies have joined the market since it was set up, raising a total of £96bn through listings and subsequent share issues. The success stories have included the likes of online clothing retailer ASOS and Majestic Wine. But there have been disasters too, including the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s, which popped in 2000. More recently, insurance software firm Quindell became the subject of a Serious Fraud Office investigation when its accounting practices were scrutinised last year.

Such incidents provide plenty of ammunition for critics, as does the overall performance of the market.

Analysis by Elroy Dimson and Paul Marsh of the London Business School for the

Financial Times last year showed that, in the previous 20 years, investors would have lost money in 72% of the companies listed on AIM, and in more than 30% of cases, they would have lost at least 95% of their investment.

Statistics like these do not put off everyone though, and some stock pickers have managed to buck the market trend, even while acknowledging it can be more risky than other markets.

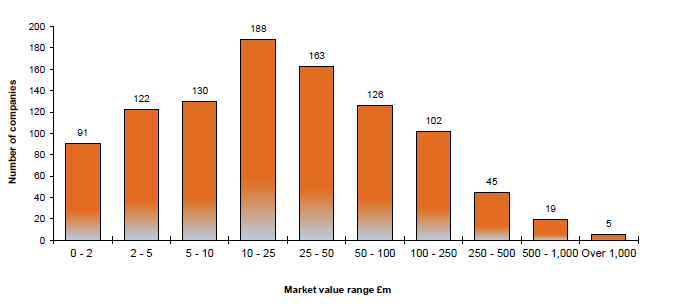

Distribution of AIM companies by equity market value

Source: London Stock Exchange

More blow-ups

Source: London Stock Exchange

More blow-ups“The overriding factor when one is investing is to have a good spread of investments, because inevitably there will be more blow-ups in the AIM market than there will be in fully listed companies,” says Paul Mumford, Senior Investment Manager at Cavendish Asset Management.

Cavendish holds between 70 and 75 companies in its AIM Fund at a time, typically investing £500,000 in each company. It launched the fund in October 2005, when the AIM All-Share Index was above 1,000 points. The index subsequently sank to 376 points in March 2009, and as of late April was around 730 points. That’s still well below Cavendish’s starting level, but Mumford says the fund has gained 60% to date, showing that there are still areas of growth.

There are numerous other funds investing in the market. Different fund managers will have different strategies and preferences in terms of sectors, the size and age of companies and whether they are already profitable or not, as befits what is something of a stock picker’s market.

“We have a heavy presence in life sciences and technology stocks within the venture capital trusts. Across the broader fund management team we’ll look at anything within reason,” says Oliver Bedford, Investment Manager at Hargreave Hale. “We don't have minimum market cap requirements, for example, and companies don't have to be profitable. Some fund managers have these kind of restrictions on their mandates, which takes them out of part of the market.”

£30.9bn

The value of AIM shares traded in 2015The trick is, of course, to find the right balance between opportunities and potential rewards. “The press tends to focus on the negative side of AIM, the risky aspect of it, and less on the good companies. There are many companies on AIM that are market leaders and growing substantially. These are very profitable businesses,” adds Bedford. “Investing in any small company carries a higher level of risk, whether it's on AIM, privately or on a crowdfunding platform. It's a different style of investment and people have to accept it comes with different risks.”

However, these days the choice of stocks from which one can pick winners rather than losers is shrinking. From 118 initial public offerings (IPOs) in 2014, in 2015 the number had dropped to 61. In the first quarter of 2016 the figure was 15, which suggests the situation this year will be much like last year. At the same time, 121 companies left the market last year and there were 39 delistings in the first quarter of this year.

The value of shares traded has also been in decline, dropping to £30.9bn in 2015 from £42.9bn in 2014. The average value of daily trades in the first quarter of this year was running at £112m, compared to £122m last year and £169m in 2014.

Mirroring the economyOn one level, the health of a stock market reflects the wider economy it serves, so it’s perhaps not hugely surprising that these numbers are currently heading in the wrong direction.

“Markets have been unsettled anyway. It's not as though we've been overrun with IPOs on the main market either,” says Gervais Williams, Managing Director of Miton Group and author of

The future is small, which predicts that AIM will be the best-performing market in the coming years. “It has been easier to finance yourself using low interest rates and suchlike. Another reason is that small companies have lower valuations at the moment. So if you’re coming to AIM, valuations aren’t especially attractive to the seller.”

15

The number of initial public offerings made in the first quarter of 2016Even so, some companies are still entering the market. Confectionery firm Hotel Chocolat Group made its debut on 10 May, and others lining up for a listing include cancer detection firm Oncimmune Holdings and miner Coal of Africa. Companies tend to be attracted by the fact that it is simpler and cheaper than listing on the main market, with far less onerous regulatory requirements.

For example, companies listing on the main market need to have been trading for at least three years, but there is no such requirement in the case of an AIM listing. In addition, on AIM there is no minimum free float of shares and no minimum market cap, companies are given longer to publish their financial results and a higher bar is set before they have to seek shareholder approval for major transactions.

Perhaps the most notable difference is that firms on AIM are regulated by their nominated advisor (Nomad) rather than by the Financial Conduct Authority, which oversees companies on the main market. Nomads are firms approved by the London Stock Exchange to guide companies through the listing process and to ensure they adhere to the rules going forward.

There are currently 39 approved Nomads, ranging from divisions of big international firms such as Deloitte, PwC and Citigroup, to smaller players like Strand Hanson and SP Angel. It is a system that is not without its flaws and the number of companies that have failed on AIM suggests that not every Nomad performs as well as they should do. “The fact that AIM funds are regulated by a Nomad broker can be a good or a bad thing, it depends on how good the Nomad is,” says Mumford.

All these differences lead to far lower costs for an AIM-listed company. A company with a market cap of between £50m and £250m could be charged up to £137,800 in admission fees for the main market but only £69,740 to join AIM. According to a

survey by YouGov on behalf of accountancy firm BDO and the Quoted Companies Alliance last year, the total annual cost of maintaining an AIM listing is around £500,000, compared to £750,000 for a main market listing.

Increased qualityAccording to some investors, the quality of new entrants is now far better on average than in the past.

“Until the 2008 crisis, AIM was largely associated with speculative companies,” says Williams. “In the past five years, the companies coming to the market have been of a completely different type. They're not speculative, they're regular companies with regular cash flow, regular profits and regular dividend flows, in many cases. The nature of the AIM market has changed.”

That in turn helps to encourage more serious investor interest. These days the investor community is made up of a wide range of brokers and investors, some of whom are trying to take advantage of various tax benefits. Since 2013, shares in AIM-listed companies can be included in an ISA portfolio. Holdings in some companies also qualify for business property relief, which means they can be exempted from inheritance tax, and there are also tax breaks for investors in smaller companies under the enterprise investment scheme.

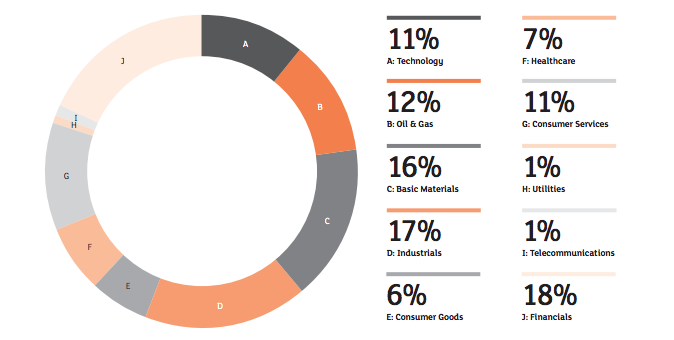

The range of companies that investors can choose from is impressively wide, in terms of both sector and scale. The ten largest companies by market cap include soft drinks maker FeverTree Drinks, building materials firm James Halstead and airline operator Dart Group. More than half the companies have market values of up to £25m, but there are more than 170 companies worth more than £100m, including five with market caps of more than £1bn.

In this respect, AIM has been far more successful than its predecessor, the Unlisted Securities Market, which ran from 1980 to 1996. It never managed to gain the same level of diversity and had a

slow demise before it was ultimately shut down due to a lack of interest relative to the main market.

Industry classification of AIM companies

Source: London Stock Exchange

A useful forumPerhaps the greatest achievement of AIM is that it has proven to be resilient. Other similar exchanges have either changed in character or disappeared. NASDAQ, for example, is now dominated by huge technology firms such as Google and Facebook. Other markets set up around the same time as AIM, such as the Nouveau Marché in Paris and Germany’s Neuer Markt, were closed in the early 2000s.

As long as it continues to provide a useful, if at times risky, forum for investors and companies to meet, AIM should continue to survive. There aren’t many other places for them to go. “I would guess that if we didn't have AIM then three-quarters of the companies would be too small to have a full quotation,” says Mumford.

A word on risk, suitability and managing inheritance tax

AIM investment is typically used for two main reasons: high growth/returns and to help manage inheritance tax (IHT). In this context, the risk and suitability parameters of AIM portfolios need careful consideration.

“For those looking to manage IHT through investment in AIM portfolios, client suitability is key. This is something that must be discussed in depth between clients and their advisers before embarking,” says Jamie Summers, Investment Management Partner at investment management and accountancy group, Smith & Williamson.

“Given that AIM-listed businesses are, by and large, smaller cap companies, AIM portfolios are considered higher risk than many other investments. Discussions regarding such investments must be seen within the context of the client’s overall financial position and take into account, for example, their total investments and other assets, financial needs, age and, of course, attitude to risk. As IHT strategies tend to be undertaken in later life, particular consideration needs to be given to escalating care costs.

“One considerable attraction of AIM investing over other IHT planning alternatives is that the client does not lose access to their capital or the income it produces.

"Diversification and, more importantly, active management of client positions, is crucial to controlling the ongoing stock-specific risk, given the huge dispersion of returns within AIM over any given period.”