Chinese stock market investors were left nursing some large losses in the opening weeks of the year. The Shenzhen Stock Exchange Composite Index fell from 2,309 points to 1,689 points over the course of January, a drop of some 27%. Its Shanghai counterpart didn’t fare much better, dropping by 23% to 2,738 points. The breakers triggered the shortest trading session in history – the markets closed just 29 minutes after they had opened. Since then, they have staged only a very limited recovery.

But investors were not the only ones hurt by the sharp drops. The country’s financial regulator was also left with some bruised pride after trying, and failing, to control the market falls.

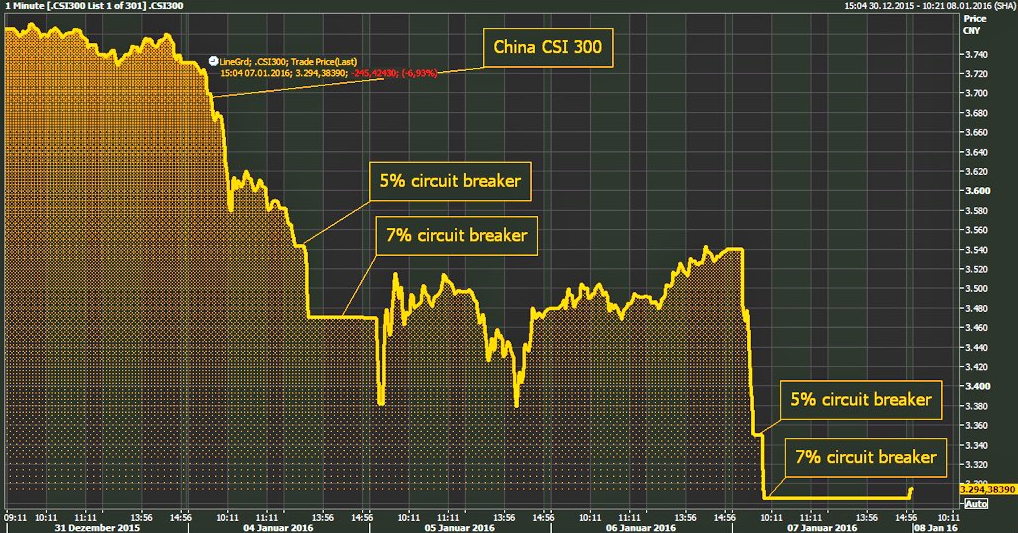

For a few chaotic days at the start of the month, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) tried to stop the slides by introducing automatic halts to trading when the markets fell too rapidly, commonly known as ‘circuit breakers’. They set the breaks at two levels. If the CSI 300 index, which includes companies from both the Shenzhen and Shanghai bourses, dropped by 5%, then trading would be halted for 15 minutes. A second break was set at 7%, at which point trading would be stopped for the rest of the day. The breakers set on 7 January triggered the shortest trading session in the Chinese markets' history – they closed just 29 minutes after they had opened. Since then, they have staged only a very limited recovery.

The experiment lasted just a few days, during which trading was brought to a halt on several occasions. The regulator retreated on 8 January, with a spokesman saying: “The negative effects of the mechanism are greater than the positive effects.”

The volatile Chinese CSI300 throughout early January

Chart by Holger Zschaepitz (@Schuldensuehner)

Speculation and rumour-mongeringThat left open the question of whether the introduction of circuit breakers was simply the wrong decision, or whether it was a good idea that was badly implemented.

One problem in China is the nature of the country’s markets and the investor bases. A lot of traders are small retail investors, something that is often associated with greater volatility. In addition, there is a severe shortage of information for investors, creating an environment in which speculation and rumour-mongering can thrive.

“Most traders are inexperienced individuals who came to the stock market with a casino mentality, trading in an environment characterised by a lack of reliable information and transparency, inadequate supervision and an inept communication strategy,” says Kamel Mellahi, Professor of Strategic Management at the UK’s Warwick Business School.

29 minutes

The amount of time Chinese markets remained open on 7 January 2016, before circuit breakers were triggeredAnother problem for the Chinese regulator was that its circuit breakers seemed to encourage rather than discourage panic selling. If the market dropped by, say, 4%, there was a clear incentive for people to sell shares, lest they get caught holding stock they didn’t want if the market continued to fall and trading was halted. Once trading resumed, any sign of further declines would encourage the same behaviour, rapidly drawing the market down to the 7% threshold.

But the experience of China does not mean that circuit breakers are inherently a bad idea. Circuit breakers came to international prominence when they were introduced on the New York Stock Exchange in October 1989, two years after the ‘Black Monday’ crash when markets around the world had quickly spiralled down. Today, they are in use in many other markets around the world, from the Indian National Stock Exchange to the London Stock Exchange.

A bit like democracy Historically, markets have been reliant on traders matching physical tickets. But this often saw tickets pile up due to the sheer number of them and, naturally, operations become inundated and bogged down. Tickets were often not matched to orders by the time the market closed, and therefore the order would be cancelled. Now that electronic trading has substantially replaced physical tickets, and high-frequency trading is transforming the floor, automated mechanisms to limit falls are arguably more important than ever. The widespread use of circuit breakers points to the fact that many regulators regard them as a useful tool. However, they have disadvantages as well as advantages, according to Matt Hurd, a consultant and former trader based in Australia.

“Circuit breakers are bad because they prevent price discovery, but they are beneficial as they force a pause to reflect in a chaotic system,” says Hurd. “Pauses don't help automated trading systems much directly, but they do give their controllers a moment to reflect on their control parameters. I like to think of circuit breakers as a bit like democracy: not a very good system, but the best of what we've tried so far.”

To break or not to break?

The positives

• Circuit breakers allow investors time to reassess their prices in times of market turbulence

• They help reduce big swings in price caused by panic-driven overreactions

• They usually allow investors time to amend or cancel standing limit orders

• By reducing data irregularities and improving the quality of information available to traders and investors, they can help promote price discovery

• They can help prevent share prices from plunging or spiking too wildly within a short time in markets that rely mainly on technology.

The negatives

• By halting trade, breaks can force investors to anticipate their trading plans, which can exacerbate order imbalances

• Portfolio managers may be unable to rebalance their portfolios once normal trading has resumed

• Price discovery is postponed, spreading the volatility over long periods of time and preventing an immediate market correction

• Circuit breakers only halt immediate trading, intensifying price changes once normal trading conditions have resumed.

Source: Arab Federation of ExchangesGiven that China has a less developed information network than other economies using circuit breakers, the retail sector is prone to overreact. It is arguably inevitable that such a large market with so many players would see growing pains on entering into market systems evolved over hundreds of years.

Whether any of the other examples of circuit breakers provide an attractive model for them to copy is open to question. Perhaps the Chinese regulator will stick with circuit breakers but revise their trigger levels. Most other markets set the breakers at higher levels than those seen on the Chinese bourses, with larger gaps between the trigger points. For example, the National Stock Exchange in India has three break points set at movements of 10%, 15% and 20% in either the BSE Sensex or the Nifty 50. Of course, if triggers are too high they will come into effect very rarely, which removes the point of them. Setting them therefore requires a delicate balancing act.

The alternativesThere are some alternatives to circuit breakers, such as discretionary trading halts, which suspend trading if there is a significant trade imbalance in a stock or an important news announcement is expected. Another tool, more often used in derivatives markets, is setting a price limit, which restricts trading to within a certain price range.

One further option is to introduce ‘sidecars’, as noted by Avanidhar Subrahmanyam, Professor of Finance at the University of California, Los Angeles, in his 2012 paper Harmonised circuit breakers, written for a UK Government project on computer trading in financial markets. This, he explains, is a system whereby “market orders are batched over short intervals and then matched against limit order books … which would potentially slow trading down and calm markets.” There is no complete halt in trade and market discovery with sidecars, but they do not protect against extreme order imbalances due to panic-driven selling by retail investors in response to rogue algorithms. A circuit breaker, on the other hand, can be designed to allow a cool-down period to mute this reaction to any anomalous algorithms.

The pros and cons of the various options means that circuit breakers are still often seen as the best option to prevent large, market-wide falls.

“There is nothing inherently wrong with circuit breakers, at least in theory,” says Warwick Business School’s Mellahi. “They have been a useful tool in managing major stock market drops. They provide a cooling-off period for reflection, obtaining better information and making rational decisions when market behaviour begins to pose a major risk. Some have criticised them for interfering with markets and argue that stocks should find their true market value, but so far, there are no better alternatives to prevent major risks as a result of sharp stock market falls.”

Learning lessonsDespite the potential benefits, the Chinese regulator is likely to be very cautious before bringing in any new circuit breakers in future. However, it does at least appear to be open to learning lessons from the events of early January.

“Wild market swings revealed our supervision and management loopholes,” said Xiao Gang, head of the CSRC, on 17 January, according to remarks quoted by the Xinhua news agency. “We will improve regulation mechanisms, intensify supervision and guard against risks so as to create a stable and sound market.”

Whatever route the CSRC decides to take, there are bound to be more lessons to learn in the future. As the regulator is discovering, managing a stock market can be as much art as science.

“The main lesson is that there is no one-size-fits-all solution,” adds Mellahi. “What worked in other countries may not work in China. There is not a playbook that the central bank or CSRC can use to weather stock market turbulences. Experimentation and learning by doing are going to be the order of day.”